Undergraduate Research Projects, 2024-2025

During the 2024-2025 academic year, Xavier's Constitution Fellows pursued research projects under the guidance of Anne Rykbost, University Archivist & Special Collections Librarian. Note that some of the following projects were also published on the Xavier Library Our History Blog. You can also view a video of the Fellows' December 4, 2024 presentation of their projects on Youtube.

The Twists and Turns of Our Constitutional Amendment

By Nick Watts, Constitution Day Fellow

Project: John Boehner and the 27th Amendment

My name is Nick Watts and I am a sophomore PPP and history double major. Unsurprisingly, I will soon be picking up Xavier’s new constitutional studies minor! Even more unsurprisingly, I love history, politics, and research. When I am able to combine all three, it becomes even more fun. Although the research can be detail-heavy at times, I am thankful that the necessary documents relevant to this project are all printed in legible English! That is more than I can say for past archival research I’ve done where it can take hours to half-decipher a single sentence.

I approached this project as the exciting opportunity that it has been to be one of the first Xavier students to delve into the John Boehner Papers. Going in, I didn’t know much about the substance or relevance of the passage of our most recent constitutional amendment. Looking back, I now have not only an appreciation for number 27 itself but for the entire amendment ratification process. Although difficult, I had no idea how truly herculean of a task it is to try to amend the U.S. Constitution. Leaving with a newfound appreciation for history is one of the things that a research project gives that can’t come from anywhere else. Spending weeks studying the intricacies of a specific concept helps build connections between larger ideas. Two previous major research projects I did on the 1862 Battle of Glorieta Pass in New Mexico and the 62nd Governor of Ohio John J. Gilligan’s passage of an income tax in Ohio brought me the same gratification. It was nice to return to this feeling.

Archivist Anne Ryckbost does an incredible job curating Xavier’s history and preserving such an impressive collection as former Speaker John Boehner’s. I wouldn’t have been able to get anywhere on this project without her and I look forward to returning to the University Archives and Special Collections for future projects to discover what other connections to national history Xavier’s past offers.

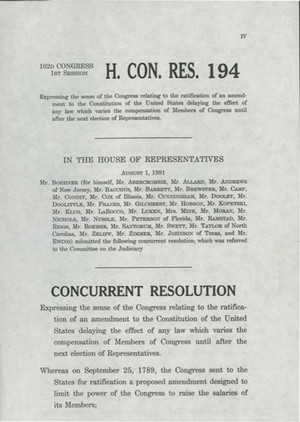

Con. Res. 194, Box 4, Folder 14, MS-009 John Boehner Papers, University Archives and Special Collections, Xavier University Library

John Boehner speaking at Xavier University Commencement, May 14, 2016, Xavier University Photographs, University Archives and Special Collections, Xavier University Library

John Boehner speaking at Xavier University Commencement, May 14, 2016, Xavier University Photographs, University Archives and Special Collections, Xavier University Library

Operation Youth: A Legacy of Leadership and Civic Education

By Savannah Hugenberg, Constitution Fellow

Constitution Day Fellow Savannah Hugenberg researched the Operation Youth program hosted by Xavier University from 1950 until 2001. Savannah is a Sophomore PPP major with a minors in psychology and economics.

Operation Youth was once a hallmark of civic education at Xavier University. This one-week summer program, initially launched in 1950, brought high school juniors and seniors together to cultivate leadership, democracy, and a deep understanding of their civic responsibilities. By offering students the chance to experience the tenets of American democracy firsthand, the program left an indelible mark on the thousands of young men, and eventually women, who passed through campus.

Historical Overview of Operation Youth

In its early years, Operation Youth combined academics, discussions on American values, and hands-on civic activities to instill democratic principles in high school boys. The program featured lectures, field trips, and observations of American institutions, all aimed at fostering civic engagement. Ultimately, the program opened its admission to women, reflecting its growth with the modernization of American culture.

The brochure for the 16th annual Operation Youth, held in 1965, provides a snapshot of the typical experience. Delegates participated in flag-raising ceremonies, attended lectures on Americanism, and engaged in discussions about democratic values and governance. The day was tightly scheduled to include a combination of assemblies, guided tours of local industries, and recreation, ensuring that the students were exposed to different aspects of American society. This gave opportunities for the young students to network, meet peers from different backgrounds, and share ideas. Operation Youth’s curriculum also incorporated discussions on family life, economics, and the relationship between business and democracy—recognizing the importance of these factors in maintaining a free society.

A Personal Reflection from Michele Watts (Speath)

Michele Watts (Speath), who participated in Operation Youth in 1985 and became a senior leader in 1988, describes the experience as one of the most impactful of her life. "It wasn’t just about politics—it was about building relationships and understanding American freedoms," she says. The program, led by the disciplined Bill Smith (Smitty), was structured and rigorous, yet it created a space for genuine connection. Michele recalls, "It felt like a retreat, where we not only learned about government but also shared personal stories. For many of us, it was the first time we felt comfortable being vulnerable."

Civic Education and Leadership Development Today

Operation Youth was more than just a summer program—it was a space for young leadership, offering invaluable experience in civic education and personal growth. The personal stories of alumni like Michele Watts (Speath) remind us that the program wasn’t only about the subjects discussed or the structure of the days. It was about forging connections and deepening an understanding of what it means to be a part of a democratic society. Though the program may not be active, the legacy of Operation Youth lives on in the lives of those who participated, who continue to live out its ideals of leadership, community, and civic engagement.

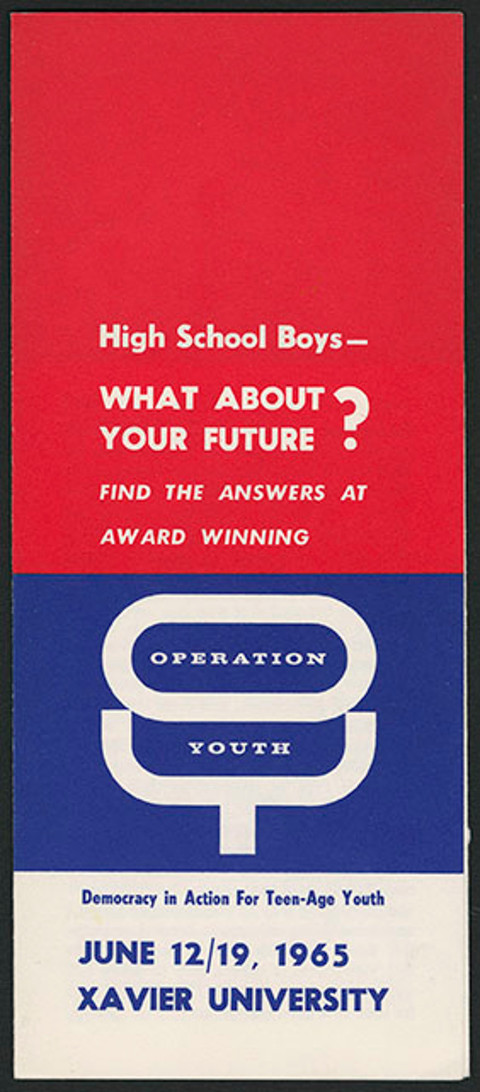

Operation Youth Brochure, 1965, Box 1, Folder 1, XUA-144 Xavier University Collection of Operation Youth Records, University Archives and Special Collections, Xavier University Library

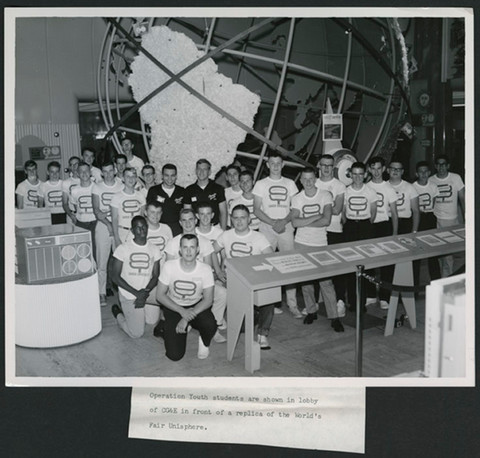

Operation Youth Participants, 2001, Box 1, XUA-148 William E. Smith Operation Youth Records, University Archives and Special Collections, Xavier University Library

Participants visit Cincinnati Gas & Electric, Box 1, Folder 5, XUA-144 Xavier University Collection of Operation Youth Records, University Archives and Special Collections, Xavier University Library

George Washington Birthday Commemoration

By Ethan Pilote, Constitution Fellow

In fall 2024, Xavier student Ethan Pilote conducted research on the annual George Washington Birthday Commemoration hosted by Xavier University in the 19th and early 20th centuries.

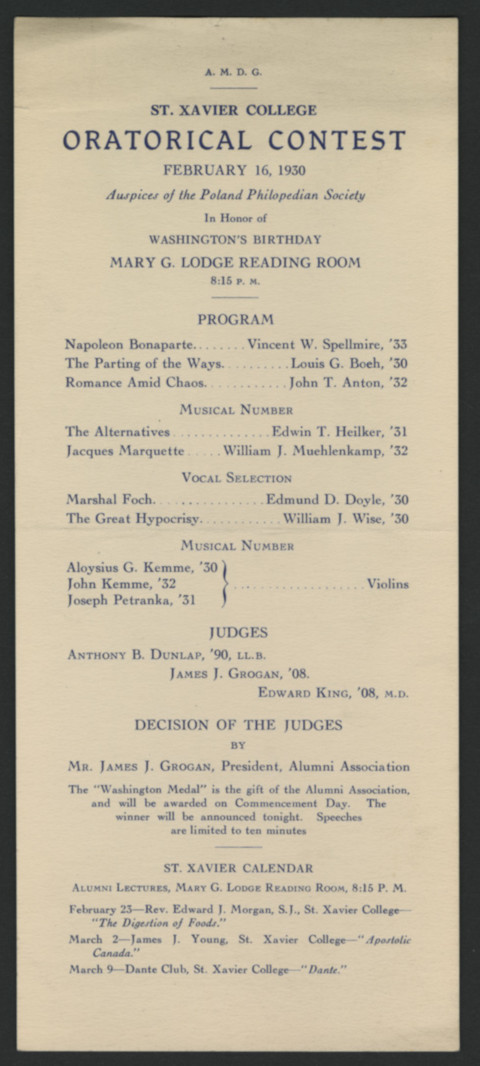

Reflecting on the history of the celebration, Pilote writes, “Beginning in 1841, the spring following the Jesuit’s assumption of the Athenaeum, the celebration of George Washington’s birthday became an annual event. George Washington was an idol within the college due to the general understanding that he was a noble American leader, known to express patriotism, and had a strong sense of civic duty. The mission behind this celebration was to push students to pursue an issue relating to the United States, promoting students to take action in society. In the early years, it was mandatory for every student to participate in or attend the commemoration featuring a contest of speeches made in honor of Washington, but as it and the school grew that was no longer an option. The majority of the early planning was done by the Philopedian Society, which met frequently throughout the year to debate current events. In 1893 the Alumni Association took hold of the event and officially introduced the Gold Medal, also known as the Washington Medal, which was gifted to the winner upon commencement. The event was held often in Memorial Hall on campus but, as popularity grew other venues would be available. In the year 1911, the celebration occurred at the Grand Hotel in Cincinnati where over 100 guests were reported.

St. Xavier College Oratorical Contest program, February 16, 1930, XUA-106 Box 6, Folder 3, University Archives and Special Collections, Xavier University Library

Students (William Roll and Bernard Gilday) debate in Conaton Board Room, February 21, 1941, XUA-125 Xavier University Photographic Negative Collection, University Archives and Special Collections, Xavier University Library

Is the Equal Rights Amendment Law? A Century of Hope, Hurdles, and Hard Truths.

By Savannah Hugenberg, Constitution Fellow

In January 2025, former President Joe Biden declared the Equal Rights Amendment (ERA) “the law of the land.” For many, it was a long-awaited affirmation of a promise made over a century ago: that equality under the law shall not be denied on the basis of sex. But bold declarations don’t always make for legal reality—and the ERA, despite recent ratifications and public enthusiasm, remains in constitutional limbo.So, is the ERA law? Not exactly. And here’s why.

A 100-Year-Old Promise

The Equal Rights Amendment was first introduced in 1923 by suffragists Alice Paul and Crystal Eastman. Its goal was simple: to guarantee that legal rights could not be denied based on sex. After the success of the 19th Amendment, many saw the ERA as the logical next step toward gender equality.

But for nearly 50 years, the amendment sat in Congress without enough traction to pass. This was no surprise—between 1922 and 1970, only 10 women ever served in the U.S. Senate. It wasn't until 1972 that Congress finally passed the ERA with overwhelming bipartisan support, sending it to the states with a seven-year ratification deadline.

Thirty states ratified it in the first year, and by 1977, 35 had signed on—just three states short of the required 38. Then momentum stalled.

Conservative Opposition

The opposition, led by conservative activist Phyllis Schlafly, argued that the ERA would actually harm women. She claimed it would erase gender roles, force women into combat, and strip away protections like spousal financial support and draft exemptions. Schlafly’s message struck a chord, especially with stay-at-home mothers and religious individuals, who feared the amendment would unravel the traditional family structure.

Religious groups—including Mormons, Catholics, and fundamentalist Christians—joined the fight, framing the ERA as an attack on biblical values. Supporters of the amendment struggled to counter these arguments, and the campaign to ratify the ERA effectively collapsed.

By the extended 1982 deadline, no additional states had ratified the amendment. In addition, five states (Nebraska, Tennessee, Idaho, Kentucky, and South Dakota) voted to rescind their earlier support. Whether states can legally do that is still unresolved—but either way, the path to ratification for the amendment was blocked.

A Legal Roadblock—And a Modern Revival

So, why isn’t the ERA law? Because the deadline expired in 1982.

Supporters argue that since Congress created the deadline, it can also remove it—retroactively. Efforts like Senate Joint Resolution 6 (of the 116th Congress) sought to do just that, but the Senate never acted. And while the House has passed similar measures in the past, none have cleared both chambers.

The legal community is divided. Some scholars say Congress has the power to validate the ERA post-deadline. Others argue it’s a constitutional nonstarter without starting the process over. In 2020, the Department of Justice’s Office of Legal Counsel issued an opinion stating that the ERA is no longer pending before the states. The National Archives, which would be responsible for certifying the ERA, confirmed it would not act without a federal court order.

In recent years, the ERA has experienced a surge of renewed interest. Fueled by the #MeToo movement, rising gender awareness, and greater female representation in government, Nevada (2017), Illinois (2018), and Virginia (2020) all ratified the ERA. That brought the total number of ratifying states to 38—technically enough to meet constitutional requirements. But if we’re going to count those three states that ratified after the deadline, doesn’t that mean we also have to reckon with the five states that rescinded their earlier support? And if we do, are we really looking at just 33 valid ratifications—well short of the required 38?

This is a legal question far above my pay grade.

So, What Now?

The future of the ERA depends on three key players:

- Congress, which could pass legislation to remove the deadline or start the amendment process anew;

- The Courts, which may eventually decide whether the late ratifications and rescissions are valid; and

- The States, where further action could signal national consensus—or deepen the divide.

Public support for the ERA remains high, and many of its intended effects have already been achieved through court decisions and legislation, particularly via the 14th Amendment’s Equal Protection Clause. But the desire to see gender equality explicitly written into the Constitution is still strong.

That said, we have to confront the truth: the ERA, as introduced and passed in 1972, is not the 28th Amendment. Unless Congress restarts the process with a new vote and timeline, it likely never will be.

Symbolism vs. Substance

The Equal Rights Amendment is a symbol of a century-long struggle for gender equality. But symbols alone cannot rewrite the Constitution. As much as the ideals behind the ERA may be admirable, we have to respect the legal process. Trying to retroactively validate a lapsed amendment, especially one with unresolved rescissions—raises serious constitutional and procedural concerns.

Until the legal barriers and uncertainties around this amendment are answered by our three branches of government, the ERA remains a promise unfulfilled, a question unanswered, and a debate far from over.

Summer 2025 Project

During the summer of 2025, Constitution Fellow Natalie Coyle conducted a number of research and writing projects under the supervision of professor Mack Mariani.

Ohio's Role in the Revolutionary War

By Natalie Coyle, Constitution Fellow

Ohio is not the first place my mind goes to when it comes to historical revolutionary war battles. I usually think of Valley Forge or Bunker Hill, but as it turns out, Ohio is rich in Revolutionary War era history. Part of the western frontier, Ohio was a crucial battleground in what historians refer to as the Western Theater of the war. The region was a land of skirmishes, forts, and complex alliances between British forces, Native nations, and American militias.

Ohio- Forgotten Frontier

As the American Battlefield Trust explains, Ohio was part of the Western Theater of the war—a region where Native American alliances, British influence, and American expansionism collided. This side of the war wasn't waged on typical battlefields, but rather through raids on villages, sieges of isolated forts, and fierce retaliations from both sides. American militias aimed to secure present-day Ohio, as Native nations fought to defend their land.

One of the best examples of this frontier warfare was the Siege of Fort Laurens in 1779. Built by the Continental Army near present-day Bolivar, Ohio, Fort Laurens was the only American fort built in Ohio during the Revolution. British and native troops laid siege on the fort in February of 1779 until March. The fort defender endured horrific conditions, starvation, and disease. What was originally supposed to be a launching point for troops headed to Detroit, now symbolically serves as a marker of how high the stakes were for claiming the region.

Logan’s Fort

Although technically just south of Ohio, at the Kentucky border, the events at Logan’s Fort had a major impact on the Ohio Frontier. The fort was besieged by a Shawnee-led force in 1777. There was steady battle for a month, until the Shawnee eventually vacated. The surviving settlers were able to retain a foothold on the frontier as the war continued.

Gnadenhutten Massacre

The Gnadenhutten Massacre occurred in 1782 in Gnadenhutten, Ohio. The Pennsylvania militia entered Gnadenhutten and convinced the villagers to surrender their arms. That night the militia imprisoned the villagers and massacred them the next day. 96 people were killed. The militia operated under the pretense of ending Native American raids, however it did not, and one would argue that it only made things worse.

Ohio is not highly recognized for its revolutionary history. Underneath the spotlight of our Founding Fathers and major battle grounds we find in our history textbooks, there are hundreds of lesser-known raids and conflicts that unfolded just like these. Although not glamorous, these battles were essential in shaping the early republic. By acknowledging Ohio’s role in this history, we honor the full scope of the fight for a nation—not only the ideals it proclaimed, but the difficult, often painful, path it took to get there.

How Xavier Celebrated the Nation's BiCentennial

By Natalie Coyle, Constitution Fellow

I, for one, had no idea that federal commissions were established to commemorate some of America’s milestone anniversaries. The Bicentennial Commission was formed in 1966, a full decade ahead of the 200th anniversary in 1976. Congress followed suit for the 250th, establishing a Semiquincentennial Commission in 2016. Historically, national celebrations have kicked off a year in advance. For the Bicentennial, the first official event was held in April 1975. Similarly, the Semiquincentennial festivities officially began this past Memorial Day.

According to the Newswire, Xavier started celebrating as soon as the school year begun in 1975 with programs and events beginning in September. I am eager to see what Xavier has planned for this upcoming celebration. From what I can gather from the school papers, campus mood seems to mirror the tone of today—economically at least. The April 1, 1976 edition of The Newswire features an Allegheny Airlines ad titled, “How to Fly Home in the Face of Inflation.” That same issue also promoted a talk by a guest economist, emphasizing that inflation wasn’t just a national problem—it was part of campus conversation too.

Much like some of today’s Semiquincentennial programs, the arts played a central role in Xavier’s Bicentennial observance. In February, Mount St. Joseph's College hosted a professor-led dialogue and American folk-dance interpretation. At Xavier, student Anita Buck reviewed the campus production of The Contrast, a satirical 1787 play that explores the difference between European and American culture. In her blunt review, Buck described it as “the most tolerable and probably the only enjoyable Bicentennial event of the year.”

What struck me most while going through the archives was how familiar it all felt. Fifty years later, students are still navigating economic pressure, still trying to make sense of national identity, still questioning how—or whether—to celebrate it. The Bicentennial wasn’t universally exciting for Xavier students, and I imagine the Semiquincentennial won’t be either. But I don't think that is necessarily a failure, but a reminder of what these celebrations are really about. Historical milestones don’t just ask us to look backward, but they invite us to look around in real time. The anniversary serves as an opportunity to reflect on: Who are we right now? What values are we choosing to live by? What is “American culture” right now?

The Pen Behind the Revolution: Mercy Otis Warren

By Natalie Coyle, Constitution Fellow

Mercy Otis Warren was a political poet and satirist during the revolutionary period. Unlike most women at the time, Warren was privileged to a private tutor in her early years, which granted her the skills and intellect to be able to publish work as eloquently as she did. Though she was a woman “stepping out of her bounds” into writing, publishing, and political life, Warren didn’t frame herself as a revolutionary feminist figure.

In all the literature, it is clear that Warren was encouraged to write by her male counterparts—her husband, James Warren and friend, John Adams. James Warren was a prominent Massachusetts politician which led to a friendship between the Warren and Adams family. Mercy and Adams eventually developed a rich intellectual friendship through letters.

Warren acted behind-the-scenes, both by choice and precedent. Most of her early work was published anonymously under a pseudonym (usually “Colombian Patriot”). Although it was common practice at the time by writers of both sexes, her anonymous publications allowed her to contribute boldly without being dismissed. Ironically, because her writing was so sophisticated and well-argued, it was often assumed to be written by a man. Politics was a man's realm, and she stepped into it because she recognized the value of overlooked perspectives. Her input was crucial in shaping the new nation.

The Warren household became a hub for intellectual gatherings between political leaders. Warren got a front row seat to the birth of a nation, listening in on Patriot conversations. That’s why in 1805, she published a three- volume comprehensive account of the Revolution titled History of the Rise, Progress, and Termination of the American Revolution. It remains one of the first histories of the period written by an American—and the first by a woman. In it, she boldly asserted, “The origin of all power is in the people, and they have an incontestable right to check the creatures of their own creation.” Her perspective was not only informed but heightened by firsthand knowledge of the events and leaders who shaped the new nation. Her work was intellectually independent, unafraid to criticize even her closest allies, and rooted in a deep belief that political power must remain accountable to the people.

Warren was also a master of satire. "The Adulateur," published in 1772, was Warren's breakthrough political satire that depicted the Massachusetts Royal Governor, Thomas Hutchinson, as the corrupt villain ruling over a fictional tyrannical kingdom. Despite publishing anonymously, its bold critique helped Warren establish herself as a strong political voice. This also marked the beginning of her influential role in shaping revolutionary thought through satire. Her more creative works made complex political ideas more digestible for those outside the circle of educated elites.

Though she never held office or held public speeches, Warren’s contribution to the American Revolution is undeniable. Her writings challenged the dominant narratives of the time, and her involvement in the political sphere challenged the societal norms of the time. Her legacy reminds us that the quiet, behind the scenes voice can leave a deep mark on history.

*****