Terms: A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z

Terms C

- Campion, Edmund

- Canisius, Peter

- Canonization

- Cardinal

- Cardinal, Fernando

- Carroll, John

- Catholic

- Catholic/Christian-Jewish Relations

- Catholic Identity

- Catholic Intellectual Tradition, The

- Christian Doctrines, Central

- Clarke, Mary Frances

- Claver, Peter

- Clavius, Christopher

- Colleges and Universities

- Colloquy, The

- Colombière, Claude la

- Common Good

- Communion of Saints

- Conciliarism

- Conferences and Retreats

- Congregation of St. Joseph,

Founding of the - Consolation and Desolation

- Conversations on Jesuit Higher Education

- Conversations on Catholic Identity E-Seminar

- Conway Institute for Jesuit Education

- Couderc, Therese

- Council of Constance and Vatican Council I

- Creation

- Cristo Rey Network

- Cura Apostolica

- Cura Personalis

- Cura Propria

- Cura Studiorum

- Cura Terrae

- Curia

Jesuit Terms C

Campion, Edmund (1540-1581)

British Jesuit; martyr; saint

William Allen's seminary for training British diocesan priests in Douai, Belgium, was the principal hope of Catholics in the England of anti-Catholic penal laws. Two of these well-trained men, Thomas Woodhouse and John Nelson, smuggled into their homeland, were captured and, while awaiting execution, asked to be admitted to the Society of Jesus. They were the first Jesuit martyrs to die in England. Allen kept urging the Jesuit superior general to establish an English Jesuit mission. After some hesitations, he did so. And therefore, in 1580, three Jesuits including Edmund Campion, disguised, landed on the coast of Kent. "All three were to know the efficiency of the English government's spy system" (Bangert, A History of the Society of Jesus [1986]).

William Allen's seminary for training British diocesan priests in Douai, Belgium, was the principal hope of Catholics in the England of anti-Catholic penal laws. Two of these well-trained men, Thomas Woodhouse and John Nelson, smuggled into their homeland, were captured and, while awaiting execution, asked to be admitted to the Society of Jesus. They were the first Jesuit martyrs to die in England. Allen kept urging the Jesuit superior general to establish an English Jesuit mission. After some hesitations, he did so. And therefore, in 1580, three Jesuits including Edmund Campion, disguised, landed on the coast of Kent. "All three were to know the efficiency of the English government's spy system" (Bangert, A History of the Society of Jesus [1986]).

It was not Campion's idea to return to England and certain death, especially not at the time Nicholas Sander was attempting (with the approval of Allen) to overthrow English rule in Ireland with the help of Spain. (The attempt ended in disaster.) But he went as asked. He lasted thirteen months before he was betrayed, arrested, tortured and in the customary manner of execution "hanged, drawn and quatered" [that is, hanged, cut down while still alive, disemboweled, and his body cut into four parts].

Before entering the Jesuits on the Continent, Campion had distinguished himself as a student at Oxford and come to the attention of Queen Elizabeth, who twice offered him prestigious offices in the Church of England, which twice he turned down. Shortly after his return to England, he issued a manifesto about his mission, now known as Campion's Brag. In it he asserted that his purpose was religious, not political. Here is his famous conclusion:

And touching our Society, be it known to you that we have made a league—all the Jesuits of the world cheerfully to carry the cross you lay upon us, and never to despair your recovery, while we have a man left to enjoy your Tyburn [place of execution in London], or to be racked with your torments, or to be consumed with your prisons. The expense is reckoned, the enterprise is begun. It is of God, it cannot be withstood. So the faith was planted, so it must be restored.

From 1880 to 1975, the Jesuits had a boarding school (secondary) for boys in Prairie du Chien, WI, named Campion Jesuit High School. The school's slogan was "Give Campion a boy and get back a man."

The residence for Jesuit scholars at Oxford is named in his honor Campion Hall.

See Waugh, Edmund Campion (1946)

Thomas M. McCoog, The Reckoned Expense: Edmund Campion and the Early English Jesuits, rev. and enl. ed. (2007).

Review of Gerard Kilroy, Edmund Campion: A Scholarly Life in The Tablet (21 November 2015).

Back to top

Canisius, Peter (1521-1597)

Dutch Jesuit; Second Apostle of Germany, [St. Boniface was the first—8th cent]; saint

The 22 year-old Peter Canisius (a Latinized form of his name), born in Nijmegen, the Netherlands, and educated at the University of Cologne, went to Mainz, Germany, to seek out Peter Faber (one of the early companions of Ignatius in Paris). Faber guided him through the Spiritual Exercises and, honoring the discernment he made during the retreat, admitted him to the Society of Jesus.

Ignatius as superior general sent him to be part of the team that founded the first Jesuit school for non-Jesuit students in Messina, Sicily. From there he was called by the pope and sent to Germany, where he spent the rest of his life writing, founding and running colleges (18), and preaching, perhaps his most important ministry. His preaching drew people back to the Catholic Church who had gone away in response to the Protestant reformers. Among the cities where he worked were Ingolstadt (Bavaria), Vienna (Austria), Prague (Bohemia), Innsbruck (Austria), and Fribourg (Switzerland).

The most famous and popular of Canisius' 37 books was the Catechism, which he composed in Latin, but which was soon translated into German. The original, intended for university students, was adapted for secondary schools and then for children just starting their religious education. All of these together had some 200 printings during his lifetime and continued to be used into the 19th century. Catechism and Canisius were synonymous.

Canonization

“Canonization” is the formal process by which someone who has died becomes a saint in the Catholic Church. Typically, this process includes four steps and is delayed until 5-years after their death. The five year delay can be waived in rare instances such as that of Pope John Paul II, whose process towards canonization started shortly after his death due to his reputation for holiness. At the first stage, when someone is initially entered into the process for consideration, the person is considered a “Servant of God." During this stage considerable investigation is done to verify the person’s reputation for holiness. When they are advanced to the second stage after this investigation is complete, they are given the title “Venerable Servant of God”. At the third stage, after the person is either declared a martyr by the pope or has been credited with proof of a miracle through their intercession, the person is considered “beatified," receives the title “Blessed", and may be venerated at the local and regional levels. At the fourth and final stage, after the person has been credited with proof of a second miracle through their intercession, they are then elevated to full “sainthood” and may be venerated by the universal Catholic Church.

Cardinal

A senior Catholic Church official, a prince of the Church and elector of the pope

Appointed by the pope, cardinals advise him when asked. Together (in number well over 100) they make up the College of Cardinals, whose major charge is to elect a new pope—bishop of Rome—when the previous one dies or resigns. Except for the patriarchs of the Eastern Catholic churches, cardinals—wherever they come from—are considered clergy of the diocese of Rome in order to be in continuity with the tradition that the clergy elect their bishop. (A cardinal who turns 80 years old ceases to be an elector.)

In addition to this crucial role, it often happens that cardinals, as bishops, head a diocese, or they may run a department of the Vatican.

Pope Francis has a kind of "cabinet" of nine representative cardinals from around the world who advise him in an ongoing way and meet with him periodically as a group.

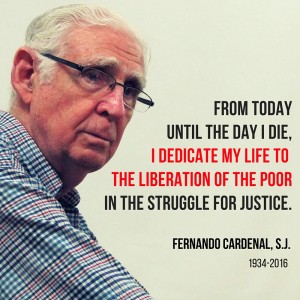

Cardinal, Fernando (1934-2016)

Nicaraguan Jesuit; advocate for the poor; architect of the Literacy Campaign and Minister of Education

Fr. Fernando Cardinal's lifelong commitment to the poor and the oppressed began as a young Jesuit living among the poor in MedellÍn, Colombia, and lasted throughout his Jesuit life.

Fr. Fernando Cardinal's lifelong commitment to the poor and the oppressed began as a young Jesuit living among the poor in MedellÍn, Colombia, and lasted throughout his Jesuit life.

Despite repeated requests from Rome that he refrain from political activity and advocacy, he remained engaged in the Nicaraguan revolution against the Somoza dictatorship. In 1979 that 46-year-long murderous regime came to an abrupt end. The U.S. Carter administration withdrew their funding, and the leftist Sandinista revolutionaries threatened to apprehend them. They simply got on a plane and left the country without further bloodshed.

In the years following the revolution, Cardinal was asked in various ways to help build the new representative government. He led the Nicaraguan Literacy Campaign (50% of the populace was illiterate) and served as the country's Minister of Education (1984-1990).

As a consequence of his commitment to live in solidarity with the poor and his refusal to abandon his work, Fr. Cardinal was dismissed from the Jesuits in 1984, only to be reinstated in 1997. During this time he continued to live in the Jesuit community compound but was technically not a member of the Society of Jesus. He went on to serve as director of the Fe y Alegría network in Nicaragua, a Jesuit network of schools for the most economically poor throughout Latin America, as well as speaking regularly to groups in Nicaragua and internationally.

Orbis Books recently published Fr. Cardinal's memoirs, Faith and Joy, written with Kathy McBride and Mark Lester, long-time friends who work for Augsburg College's Center for Global Education in Nicaragua.

The following video recording was produced by John Carroll University, where Fr. Cardinal visited in 2014 and shared his story of working for justice with students and faculty; the talk is long, detailed, and inspiring:

—The Ignatian Solidarity Network [edited and augmented by George W. Traub]

Carroll, John (1735-1816)

American; first bishop of U.S.; founder of Georgetown University

Born in the Maryland colony and educated in Europe, where he joined the Jesuits. With the pope's suppression of the Society of Jesus in 1773, he returned to his family's plantation in Maryland and ministered to people in what is now the District of Columbia. In 1786 he was appointed superior of the clergy in the U.S., and he moved to found Georgetown Academy (later University) in 1789 to provide intelligent, educated laity for the new country. Carroll was appointed Bishop of Baltimore and gathered around him fellow ex-Jesuits to form The Catholic Gentlemen of Maryland. His diocese was all of the United States.

Born in the Maryland colony and educated in Europe, where he joined the Jesuits. With the pope's suppression of the Society of Jesus in 1773, he returned to his family's plantation in Maryland and ministered to people in what is now the District of Columbia. In 1786 he was appointed superior of the clergy in the U.S., and he moved to found Georgetown Academy (later University) in 1789 to provide intelligent, educated laity for the new country. Carroll was appointed Bishop of Baltimore and gathered around him fellow ex-Jesuits to form The Catholic Gentlemen of Maryland. His diocese was all of the United States.

As leader of the American Catholic Church, Carroll was centuries ahead of his time. He advocated liturgy in the vernacular, participation of the laity in the running of the church, and in the selection of bishops interference neither by the state nor by church administration in Rome.

In 1814, 2 years before his death, the Jesuits were re-established; and Carroll anticipated an influx of new Jesuit teachers for his favored project, Georgetown.

Catholic

The word comes from the Greek meaning "through the whole," that is "universal," "world-wide," "all inclusive." This is the meaning when the word starts with a lower-case c as in "We need to become more catholic in our attitudes." In talking about the "Catholic Church," members often mean the "pope and the bishops" or "the Vatican." But Vatican Council II, in its Constitution on the Church, used several other terms with inclusive meanings like "the People of God."

For people in Jesuit education, the question is often "Are we maintaining and enhancing our 'Catholic Identity'?" Despite the fact that there are entire books devoted to the question, the answer is not easy to come by. A careful reading of the various essays on "The Issue of Catholic Identity" in A Jesuit Education Reader seems to indicate both that much is being done and that more needs to be done.

Some people, when they hear the word Catholic, think "thought control" or "one-issue myopia." Even if there is some justification for their attitude, they are probably operating with little more than news-media knowledge of Catholicism, with no sense of the rich and diverse Catholic intellectual tradition, the artistic tradition accompanying it, the Catholic social justice tradition since 1891, or the witness of heroic lives lived in the past and especially in our own time.

After the Council of Trent (1545-1563) and 16th-century Catholic reform, for centuries prior to the Second Vatican Council (1962-1965), there was a homogeneity to Catholic belief, theology, and practice in most of Europe and America. That kind of unity now feels long gone, for there is currently such a broad spectrum—one might almost say polarization—of Catholic theologies and spirituality that some Catholics feel more connected to some Protestants than they do to other Catholics. It seems likely that the Catholic unity of the future will be far from uniformity, but rather will incorporate some of present-day pluralism within its unity.

Read more on the term "Catholic"

Catholic/Christian-Jewish Relations

Catholic Identity

The essential characteristics of a Catholic university were outlined in an apostolic constitution issued by Pope John Paul II in 1990, Ex Corde Ecclesiae ("From the Heart of the Church") which defines the catholicism of Catholic institutions of higher education through their shared values, identity, and mission; it states:

Since the objective of a Catholic university is to assure in an institutional manner a Christian presence in the university world confronting the great problems of society and culture, every Catholic university, as Catholic, must have the following essential characteristics:

- A Christian inspiration not only of individuals but of the university community as such;

- A continuing reflection in the light of the Catholic faith upon the growing treasury of human knowledge, to which it seeks to contribute by its own research;

- Fidelity to the Christian message as it comes to us through the Church;

- An institutional commitment to the service of the people of God and of the human family in their pilgrimage to the transcendent goal which gives meaning to life." (nn 13)

"For more information on "Foundations of Xavier University's Catholic Identity"", See "Xavier's Catholic Identity", and see our Resource page

Back to top

Catholic Intellectual Tradition, The

Theologian Monika Hellwig (1929-2005) defines the Catholic Intellectual Tradition in terms of its content and also its approach to knowledge, to reality. Content—this includes not just great written works like Chaucer's Canterbury Tales, Dante's Divine Comedy, Shakespeare's plays (especially great tragedies), Jane Austen's Pride and Prejudice, G.M. Hopkins's poetry (especially "The Wreck of the Deutschland"), Zora Neale Hurston's Their Eyes Were Watching God, Georges Bernanos's Diary of a Country Priest, and Teilhard de Chardin's The Human Phenomenon (the recent English re-translation), but also great works of art—music, painting, stained glass, sculpture, and architecture. Approach to knowledge, to reality—it recognizes the continuity of faith and reason, respects the cumulative wisdom of the past, has an anti-elitist bent, pays attention to how knowledge is used (for good or ill), works toward the integration of knowledge, and operates out of the "sacramental principle" (all of creation can lead us to the sacred, to God).

See Monika Hellwig, "The Catholic Intellectual Tradition in the Catholic University" in A Jesuit Education Reader.

Christian Doctrines, Central

The central Christian doctrines are Trinity, Incarnation, and Grace. In the doctrine of the Trinity, with its "threeness" in one God, many theologians see the foundation for the call to human beings (God's creation) of community, equality, and self-giving love (see the entry "God," paragraph 2). Though many can recite the Christian creed, they can fail to understand the implications of the Incarnation, God's becoming fully human in Jesus. Thus God is committed to the human enterprise, and by becoming more and more human—our vocation in Jesus—we become more like God (see the entry "Judaeo-Christian Vision," paragraph 3 [God has freely chosen . . . .] and "Jesus," paragraph 1). Grace tells us about the gratuitous character of God's love and salvation; we can't earn God's love, but we don't have to. God gives it freely, unconditionally.

See "Trinity"

See "Incarnation" and See "Incarnation, Why the."

See "Grace"

Back to top

Clarke, Mary Frances (1803-1887)

Founder, Sisters of Charity of the Blessed Virgin Mary (Dubuque, Iowa)

Mary Frances Clarke, Dublin-born founder of the Sisters of Charity of the Blessed Virgin Mary, was a young woman of 31 years when she and four companions immigrated to Philadelphia in 1833. In leaving Ireland they listed their occupation as religious. In Philadelphia they encountered Rev. Terence J. Donaghoe, a benefactor, colleague, mentor and friend and who was among the first to affirm their religious calling. On November 1, 1833, they became the Sisters of Charity of the Blessed Virgin Mary.

Mary Frances Clarke, Dublin-born founder of the Sisters of Charity of the Blessed Virgin Mary, was a young woman of 31 years when she and four companions immigrated to Philadelphia in 1833. In leaving Ireland they listed their occupation as religious. In Philadelphia they encountered Rev. Terence J. Donaghoe, a benefactor, colleague, mentor and friend and who was among the first to affirm their religious calling. On November 1, 1833, they became the Sisters of Charity of the Blessed Virgin Mary.

While serving in Philadelphia, the sisters received a visit from Jesuit Pierre De Smet. His compelling accounts of life on the American frontier persuaded them to accept the invitation of Bishop Mathias Loras to minister in the remote Iowa Territory. In 1843 the first group of sisters journeyed with Bishop Loras to Dubuque, Iowa; the rest of the Community followed several months later. They were soon caught up in the hardships and hopes of the settlers, sharing the struggles of prairie families, farmers and lead miners. The fledgling Community began opening schools along the Mississippi River, east to Chicago (at the invitation of the Rev. Arnold Damen, SJ in 1867) and west to San Francisco and Phoenix. Each newly-established Mission carried reminders of Mary Frances Clarke's urging: "Keep our schools progressive with the times in which we live in inventiveness and forethought."

When Father Donaghoe died in 1869, Mary Frances Clarke assumed full leadership, renewing efforts to preserve the identity, integrity and purpose of her community. She was among the first women to seek incorporation in the state of Iowa (September 30, 1869). Thanks to her initiative and the counsel of Peter Koopmans, SJ, many of his brother Jesuits and other friends of the Community, the Rule of the Sisters of Charity of the Blessed Virgin Mary received final approbation from Pope Leo XIII on March 15, 1885.

Mary Frances Clarke died peacefully on December 4, 1887, having her request honored that no BVM history be written during her lifetime. At that time, the 499 living members of the Community administered forty parish schools and nine boarding academies for young women. Throughout her life she had urged the sisters to welcome all students, regardless of religious affiliation or ability to pay. She trusted Community members to become mature women, open to the changing face of ministry, able to adapt, to improvise, to develop lifestyles and educational methods uniquely suited to the needs of the times and the challenges in church and society. By encouraging the sisters to "incite" their students to think, generations of her followers both women and men continue to become leaders whose gifts and energies impact spiritual, intellectual, creative, technological and many other frontiers unforeseen by that long-ago circle of friends from Dublin.

JH

Claver, Peter (1580-1654)

Spanish (Catalan) Jesuit; "slave of the slaves forever"; saint

As a young Jesuit scholastic, Peter Claver studied at the Jesuit college in Palma on the island of Majorca. There he became good friends with the wise and holy brother doorkeeper, Alphonsus Rodriguez. Alphonsus encouraged him to consider going on mission to the New World for his life's work. And that is what Peter did.

In 1610, he sailed across the Atlantic to Cartagena, Colombia, infamous for being the chief slave market of South America. There he was trained for ministry with the enslaved people from West Africa by an older Jesuit, Alfonso Sandoval, a great spokesman for the dignity of the slaves. After ordination, then, Claver, binding himself by vow to be "slave of the slaves forever," carried on a tireless ministry of compassion and care for nearly 40 years. He met the slave ships, descended into the stinking holds filled with poor, frenzied, distressed [human beings,] brought physical relief by his practical nursing in a spirit of tenderness and spiritual support with the gift of faith (William Bangert, A History of the Society of Jesus [1986]).

Clavius, Christopher (1538-1612)

German Jesuit; mathematician; creator of the present calendar

For 45 years Christopher Clavius (Christoph Klau in German) taught mathematics at the Roman College (in the 16th century, the premier seat of Jesuit higher education). He won the respect and friendship of virtually every significant mathematician and astronomer of his day. He was a life-long friend of Galileo. He exerted a wide influence on the schools of Europe as well as those in China through his Jesuit pupils laboring there.

For 45 years Christopher Clavius (Christoph Klau in German) taught mathematics at the Roman College (in the 16th century, the premier seat of Jesuit higher education). He won the respect and friendship of virtually every significant mathematician and astronomer of his day. He was a life-long friend of Galileo. He exerted a wide influence on the schools of Europe as well as those in China through his Jesuit pupils laboring there.

“Clavius Crater” a large crater in the moon’s southern hemisphere was named after him. On Oct. 26,2020 NASA announced the discovery of water on the moon – specifically in and in and around the Clavius Crater.

Clavius's best-known contribution was his reform—at the request of Pope Gregory XIII—of the Julian calendar, which gave a year 11+ minutes longer than the actual solar year. The new Gregorian calendar was not accepted everywhere. In various parts of Europe, people broke windows in Jesuit residences as a protest. The Orthodox Church saw the new calendar as a Roman intrusion (which it was), and Protestant countries were reluctant to accept any decree from a pope. England did not change to the new calendar until 1751, while Orthodox Russia would require the Bolshevik revolution to change. (MacDonnell, Jesuit Family Album)

The Clavius Group of mathematicians, founded by a number of Jesuits in 1963 (but soon joined by other religious and lay colleagues), gather every summer (along with spouses and children) at a different university to work together in keeping with the behest of their namesake: "Let an academy be formed for the advancement of mathematics" (Christopher Clavius [1596]).

Colleges and Universities

Homepages

See Jesuit Colleges and Universities

Colloquy, The (from the Spiritual Exercises)

Often in the Spiritual Exercises, Ignatius recommends concluding a time of prayer with a colloquy, a brief conversation with God or Jesus or a saint "as one friend speaks to another." The suggestion implies that the prayer, though all through addressed, say, to God, can at the end become less formal, more natural and more familiar, friendly.

At key times in the Exercises Ignatius suggests a specific content for the colloquy, usually asking for some grace or favor.

Colombière, Claude la (1647-1682)

French Jesuit; "faithful servant and perfect friend of Jesus"; saint

A native to France, at age 17, Claude la Colombière entered the Jesuits at Avignon. Once he was ordained, Colombière began teaching and taught at the Jesuit College in Lyons. He preached and served as a moderator. In 1674, he was made superior at the Jesuit house at Paray-le-Monial, France, and spiritual director of St. Margaret Mary. In that same year, Colombière took a vow to observe the Rule and Constitutions of the Society of Jesus. He then became the rector at the Jesuit College at Paray-le-Monial in 1675. Soon after, he was sent to England as preacher for the Duchess of York. Colombière was an active missionary in both France and England. Unfortunately, he was arrested as a conspirator in England and sent to prison. Since he was the preacher for the Duchess of York, he was freed from death and returned to France.

Common Good, The

A concept traceable back to Augustine of Hippo (354-430) and Thomas Aquinas (1225-1274) and in modern times to the church's social teaching from Leo XIII's Rerum novarum (1891) to the Second Vatican Council's "Church in the Modern World" and several encyclical letters of John Paul II (1978-2005). The concept is amenable to other religious traditions and to the ethics of humanist philosophy as well. It teaches that when we care for our neighbors as ourselves, all of us live better lives (not just the few). Unfortunately, many of our American people—including ones marginally well off—do not believe this teaching. Hurting and angry, they allow themselves to be used against their own self-interest by the greedy and most powerful.

While charity for the least fortunate is good and important, the common good is best applicable when eveyone is able to make their own donations to social and economic life.

Back to top

Communion of Saints

In Orthodox, Roman Catholic, and Anglican Christianity, the belief that there is a real and powerful solidarity between those who have gone before to God (saints "canonized" [i.e. declared so by the church] and "uncanonized") and those still on their pilgrim way (Paul refers to the latter as saints in his letters).

Conciliarism

See "Council of Constance and Vatican Council I"

Congregation of St. Joseph, Founding of the

The Congregation of St. Joseph began in 1650 in a small town in south-central France called Le Puy-en-Velay. There a Jesuit priest, Jean Pierre Medaille (1610-1669), helped found a community of six women who shared his vision of the needs of the church and society and who wanted to support each other in responding to those needs.

At that time, France was a country ripe for the revolution that was to sweep over it in the next century. For many years, the country had been torn apart by wars that left women widowed and children orphaned and their villages and towns ruined by plundering armies. Economic conditions took the heaviest toll upon the most vulnerable in society. Prisons were filled with debtors. Aware of the deplorable conditions, the first Sisters of St. Joseph heard God's call to be instruments bringing about unity in a broken world.

Up to that time, religious life for women was limited to cloistered life. Bishop Henri de Maupas of Le Puy offered his patronage and ecclesiastical sponsorship of the small community of six and, on October 15, 1651, received their commitment to do apostolic work as religious for his diocese. By the time of the French Revolution almost 150 years later, there were some 30 communities of St. Joseph that had formed in France, generating new life in the church with apostolic religious life for women.

Grace Skalski, CSJ

See "Fontbonne, Mother St. John"

Consolation and Desolation

In the teaching of Ignatius, spiritual consolation consists of any movement of heart and mind that leads to an increase in faith and hope and genuine love of self and others. Spiritual desolation is just the opposite: any movement that leads to a decline in faith and hope and genuine love, to selfishness, to fear and discouragement that keep one from doing good. When one is experiencing desolation, Ignatius teaches, one should not change any previous decision or come to a new decision. In a second set of guidelines for discernment, Ignatius warns that the "bad spirit" can use apparent but false consolation to lead a person to evil under the guise of good.

Conversations on Jesuit Higher Education

Conversations is published bi-annually by the National Seminar on Jesuit Higher Education, which is jointly sponsored by the Jesuit Conference Board and the Board of the Association of Jesuit Colleges and Universities. View issues from the 1992 inaugural edition to the current current edition.

Conversations on Catholic Identity at a Jesuit University: An E-Seminar

For more information on the E-Seminar, click here.

Conway Institute for Jesuit Education

The Ruth J. and Robert A. Conway Institute for Jesuit Education at Xavier University is a center of distinction, assisting educators in transforming students intellectually, morally, and spiritually in the Jesuit, Catholic tradition, while appropriating Ignatian pedagogy and spirituality in today's world. The institute reaches beyond the Xavier campus with pedagogical innovations communicated locally, nationally, and internationally.

Watch a video introduction to the institute here.

Find more information about the Institute here.

Couderc, Thérèse (1805-1885)

Co-Founder of the Congregation of Our Lady of the Retreat in the Cenacle (Cenacle Sisters)

Marie-Victoire Couderc was born on February 1, 1805, in the mountain village of Le Mas in southern France. She was the second eldest of twelve children. Although she had no formal classroom education until she was seventeen years old she developed a deep love of God from her parents and learned to read and write from the tutor her parents engaged for their family. In 1825 Marie-Victoire participated in her parish's first mission since before the beginning of the French Revolution. During the mission she expressed her desire to enter religious life to Fr. Stephen Terme, one of the priests leading the mission. This missionary encouraged her in spite of her father's immediate refusal to give her his blessing. Nearly one year later, in January 1826, Marie-Victoire left her family and joined the little community of sisters Fr. Terme had founded. Two months later she received the habit and the name Sister Therese.

Marie-Victoire Couderc was born on February 1, 1805, in the mountain village of Le Mas in southern France. She was the second eldest of twelve children. Although she had no formal classroom education until she was seventeen years old she developed a deep love of God from her parents and learned to read and write from the tutor her parents engaged for their family. In 1825 Marie-Victoire participated in her parish's first mission since before the beginning of the French Revolution. During the mission she expressed her desire to enter religious life to Fr. Stephen Terme, one of the priests leading the mission. This missionary encouraged her in spite of her father's immediate refusal to give her his blessing. Nearly one year later, in January 1826, Marie-Victoire left her family and joined the little community of sisters Fr. Terme had founded. Two months later she received the habit and the name Sister Therese.

When she was twenty-three years old, Terme appointed Therese superior of the little community he brought to the mountain village of LaLouvesc to offer accommodations for women pilgrims coming to the shrine of St. John Francis Regis. Therese served as superior of this community for ten years. During these years the three dimensions of the congregation's Mission as we know it today took root: prayer, community and ministry lived in the spirit of the first Cenacle in Jerusalem.

When he made his retreat in 1829, Stephen discovered the Spiritual Exercises of St. Ignatius of Loyola. He was so enthusiastic about them that he immediately introduced them to Therese's community and directed the sisters to use them in their ministry. Through the Spiritual Exercises Stephen and Therese introduced the community to the great current of Ignatian spirituality which continues to mark the essential aspects of the congregation's life. Fr. Terme died unexpectedly on December 12, 1834. In his Will he confided the future of the community to the Society of Jesus, who had assisted him in the religious formation of the community. Mother Therese and her community responded with deep faith and unwavering trust in God's providential love for her community.

During the later years of her life Mother Therese witnessed the expansion of her community in France and beyond its borders, When chronic illness prevented her from being actively involved in the ministry of the community, she continued to participate in its mission through her prayer, physical suffering, and wholehearted self-surrender to God.

Therese Couderc died in Lyon on September 26, 1885. When she was canonized on May 10, 1970, Pope Paul VI said of her, "Humble among the humble. She lived her life most humbly." These few words summarize her spirituality, a spirituality rooted in the love of God, the goodness of God, and the will of God; a spirituality marked by a passionate love for Jesus Christ and a burning desire to make Him known and loved. The true testimony of Therese's spirituality is the enthusiasm with which the Cenacle Sisters continue to live the Mission of the Congregation she and Stephen Terme founded. In addition to the sisters the congregation has other forms of association. Cenacle Auxiliaries are vowed women who live Cenacle spirituality in the secular world. Cenacle Affiliates/Companions are women and men, single or married, who also live Cenacle spirituality in their daily lives all for the greater glory of God!

Back to top

Council of Constance (1414-1418) and Vatican Council I (1870)

These two ecumencial councils are treated here together because they seem to teach contradictory forms of Roman Catholic Church governance and authority—Constance being a prime instance of "conciliarism" and Vatican I of papal absolutism. The histories of these councils are especially relevant to our times, when Pope Francis is tryring to reestablish more collegial forms of governance in keeping with the teaching of Vatican II after his two predecessors downgraded collegiality in favor of more absolute papal authority.

The Council of Constance (a city in southwestern Germany) was called in a time of major crisis with three different claimants to the papacy. In contrast to previous general councils and the subsequent Council of Trent, it had a very high level of participation—patriarchs, cardinals, and hundreds of bishops, abbots, and priors, doctors of theology and doctors of church and civil law—no doubt owing to the dire situation of the church. In its decree Haec Sancta Synodus ("This Holy Synod"—1415) the council drew on the synodal or conciliar way of governance practiced in the early church and on elements of medieval canon (church) law. It taught that in certain critical cases a general ("ecumenical") council has a jurisdictional authority superior to that of the pope and can even depose a pope. Acting on its decree, Constance deposed John XXIII (the one who had called this council, not the one who called Vatican II in the mid-20th century), invited the other two claimants to resign, which one did (Gregory XII), deposed the other (Benedict XIII), and then later elected a new pope, Martin V.

One school of interpretation of Constance claims that the early part of the council, including the decree Haec Santa Synodus, was invalid (some even said heretical) because it was never approved by the pope. But that position labors under a major difficulty. It would invalidate not only the decree but the actions following upon it. The deposition of John XXIII would be null and void and so the subsequently elected pope, Martin V, and his successors all the way down to the present would be illegitimate. Perhaps that is why the conciliarist position continued to have proponents in northern Europe, for instance, and especially at the University of Paris (the "Sorbonne") down through the centuries in spite of official attempts to descredit it as invalid or heretical or simply to ignore it.

The papacy of the past 600 years, starting with Martin V himself, has not doubted its absolute authority. And the decree Pastor Aeternus of Vatican I (1870), which enunciated a (limited) papal infallibility, simply confirmed a jurisdictional authority of the papacy it assumed to be absolute. The few dissenting voices were laughed at or shouted down. It was a time when personal sympathy for the pope (Pius IX), who had recently lost his "temporal" power (the Papal States) in the political unification of Italy, was high. Apparently none of the assembled bishops raised the objection that the absolutism of Pastor Aeternus might be incompatible with the conciliarism of Haec Sancta Synodus (though Henri Maret, dean of the theological faculty of the Sorbonne, had in a two-volume work (1869) presented the case for Constance and conciliarism as a memorandum to the forthcoming council).

Oakley, "Authoritative and Ignored: The Overlooked Council of Constance," Commonweal (October 24,2014)

Creation (Genesis, chs. 1 and 2)

Creation is the Judaeo-Christian teaching that God is the origin (and the destiny) of the whole universe. Chapters one and two of Genesis, the first book of the Hebrew and Christian bible, teach this truth of creation and creatures in story form. Paying attention to the form is important for a correct understanding of what is meant. This is not history (a category unknown until long after the bible was written), not an account of a one-time event (seven days), but story truth which says that the whole universe is God-made and fundamentally good. Rather than a one-time event, creation is an ongoing, constant process. God is the only necessary one; creatures are radically limited and dependent on God's constant creation or we would fall into nothingness.

The understanding of creation as constant is important for avoiding a frequently held but wrong notion of miracle whereby God sometimes enters into the world and suspends its laws. God is always in the world as constant creator. This correct understanding of God's relation to the world is called panentheism (God in all—not pantheism, which would mean that everything is God).

Cristo Rey Network

An ever-growing nationwide network of college preparatory high schools for economically disadvantaged, inner-city students, modeled on the original Cristo Rey school founded by the Jesuits in Chicago's Pilsen neighborhood in 1996. The network describes itself as "Schools that Work"; the students all work one day a week for some cooperating company, earning a large part of the cost of their education, and go to school four days.

While the original Cristo Rey school in Chicago's Pilsen neighborhood (Mexican American) was the initiative of the Chicago Province Jesuits (1996), the majority of CR Network schools are now sponsored by other religious communities or by Catholic dioceses.

Cura Apostolica

Latin for "apostolic care" or "care for the organization"

The term cura apostolica is the counterpart to cura personalis and, as that refers to the personal care of individuals, this one is concerned with the care of an individual's apostolate or ministry or with that of a given corporate apostolate.

Coining and use of the term probably originate with Jesuit leadership and date to post-Vatican II times, but the reality of apostolic care goes all the way back to the Jesuit Constitutions (their developmental organization has everything leading up to the conduct of Jesuit ministry) and to the exchange of letters between Jesuits spread out around the world and Ignatius in Rome offering care and guidance. In both the Constitutions and these letters one finds strong, clear principles combined with the freedom to carry them out—or even change them—according to local circumstances.

The exercise of cura apostolica in the world of Jesuit higher education today falls not just on the "sponsoring" Society of Jesus but on all engaged in the work—the trustees, the presidents and other administrators, the faculty and the staff—an increasing number of whom are not Jesuits.

Cura Personalis

Latin meaning "care for the [individual] person"

A hallmark of Ignatian spirituality (where in one-on-one spiritual guidance, the guide adapts the Spiritual Exercises to the unique individual making them) and therefore of Jesuit education, where the teacher establishes a personal relationship with students, listens to them in the process of teaching, and draws them toward personal initiative and responsibility for learning [see "Pedagogy, Ignatian/Jesuit"].

This attitude of respect for the dignity of each individual derives from the Judeo-Christian vision of human beings as unique creations of God, of God's embracing of humanity in the person of Jesus,

and of human destiny as ultimate communion with God and all the saints in everlasting life.

Cura Propria

Latin meaning "care for oneself"

Coining and use of the term originated at the 2021 ‘Commitment to Justice Conference’ at which Debra Mooney, PhD offered it as “A New Ignatian Virtue Necessary for the Promotion of Justice and the Universal Apostolic Preferences.” She states that significant reserves of spiritual, psychological and physical energy and wellness are so important in being effective educators and ‘people for and with others’ that self-care is an honorable and essential Ignatian value.

Cura Studiorum

Latin meaning "care for the plan of studies"

Coining and use of the term originated in 2022 by Dr. Colleen Hanycz, Fr. Daniel McDonald S.J. and Dr. Debra Mooney to underscore the distinctive character of Jesuit education. In “More Ignatian care for educational excellence: Cura Studiorum and Cura Propria,” a web feature in Conversations in Jesuit Higher Education, they note that, “This [academic] care extends beyond cura personalis, underlining that our care for the entire person necessarily directs our attention to the intellectual environment in which that [student] is immersed.”

Cura Terrae

Latin meaning "care for the earth"

Introduced in Do You Speak Laudato Si’?: A Desktop Primer in 2023, Debra Mooney, PhD coined and used the term to complement other important ‘caring’ qualities for educational excellence in the Jesuit Catholic tradition: cura apostolica (the institution), cura personalis (the whole unique person), cura propria (oneself), cura studiorum (the plan of studies). See Cura Terrae: A 5th care for excellence in Jesuit education presented at the 2024 AJCU Faith, Justice and Reconciliation Assembly, July 2024.

Curia

The Jesuit General Curia in Rome is the center of global governance of the Society of Jesus (see also the global web page).