Terms: A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z

Jesuit Terms R

Terms R

- Rahner, Karl

- Ramos, Julia Elba

- Ramos, Cecilia

- Ratio Studiorum

- Reconciliation

- Rector

- Redemption in Christ

- Reform of the Church

- Regency

- Regis, John Francis

- Reinert, Paul

- Religion and Science Debate

- Religions, Non-Christian

- Religious Order/Religious Life

- Restoration of the Society of Jesus

- Retreat Centers

- Review for Religious

- Rhodes, Alexander

- Ricci, Matteo

- Rodriguez, Alphonsus

- Romero, Oscar

- Ruiz de Montoya, Antonio

Rahner, Karl (1904-1984)

German Jesuit; father of Catholic theology in the 20th century

Did doctoral studies in the history of philosophy at the University of Freiburg, but his dissertation on Thomas Aquinas's epistemology (later published as Spirit in the World) was rejected by a professor whose only claim to fame now is that he rejected Rahner's dissertation.

Did doctoral studies in the history of philosophy at the University of Freiburg, but his dissertation on Thomas Aquinas's epistemology (later published as Spirit in the World) was rejected by a professor whose only claim to fame now is that he rejected Rahner's dissertation.

In his teaching (at Innsbruck, Munich, and Münster) and writing over nearly 50 years, he re-did the long tradition of Catholic theology in a way that required much of his listeners and readers intellectually, but still "spoke" to their hearts and touched their existential reality and need. He was a poet in his own unique style of prose.

He was a commanding theological presence at Vatican II (1962-65). And for many in this country, reading his works as they were translated into English after the council enabled them to recognize him as the source of many of the council's ideas, one who had prepared the way for that great revolution in official Catholic theological thinking.

(Loyola Press, 2004).

Ramos, Julia Elba and Cecilia Ramos

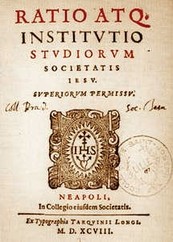

Ratio Studiorum

Latin for "Plan of Studies"

A document, the definitive form of which was published in 1599 after several earlier drafts and extensive consultation among Jesuits working in schools. It was a handbook of practical directives for teachers and administrators, a collection of the most effective educational methods of the time, tested and adapted to fit the Jesuit mission of education. Since it was addressed to Jesuits, the principles behind its directives could be assumed. They came, of course, from the vision and spirit of Ignatius. The process that led to the Ratio and continued after its publication gave birth to the first real system of schools the world had ever known.

A document, the definitive form of which was published in 1599 after several earlier drafts and extensive consultation among Jesuits working in schools. It was a handbook of practical directives for teachers and administrators, a collection of the most effective educational methods of the time, tested and adapted to fit the Jesuit mission of education. Since it was addressed to Jesuits, the principles behind its directives could be assumed. They came, of course, from the vision and spirit of Ignatius. The process that led to the Ratio and continued after its publication gave birth to the first real system of schools the world had ever known.

Much of what the 1599 Ratio contained would not be relevant to Jesuit schools today. Still, the process out of which it grew and thrived suggests that we have only just begun to tap the possibilities within the international Jesuit network for collaboration and interchange. [See also "Education, Jesuit" and "Pedagogy, Ignatian/Jesuit."]

- The Ratio Studiorum

- The Curriculum Carries the Mission (2008)

By Claude Pavur, S.J. - The Origins of Jesuit Education

Matt Dunch, S.J.

Reconciliation

Christian reconciliation relates to atonement, the repair of wrongdoings, and the making of right relationships. Superior General Fr Arturo Sosa believes that “true reconciliation demands justice.” Upon his election in 2016, he charged Jesuits to be On a Mission of Reconciliation and Justice; since that time, there has been particular attention on race relations and environmental care. (DM)

Rector

The head of a major Jesuit community within a province.

Redemption in Christ

See "Salvation in Christ"Reform of the Church

At the time of the Second Vatican Council (1962-65), a topic came into Catholic discourse that would have been unspeakable or even unthinkable for centuries before: reform of the church. That was a key Protestant idea, and therefore to be avoided at all costs. The church was a "perfect society" and didn't need reform and renewal. But the council dissolved that inhibition. Even with the tendency of the immediately past papacies to return to pre-Vatican II ways, Pope Benedict spoke to Vatican officers in late 2005, telling them that the council needed to be interpreted through a "hermeneutic [interpretative principle] of reform."

It is hard to find follow-up reform practices on the part of the Vatican. Still, the Australian Jesuit theologian Gerald O'Collins, who spent most of his life teaching and writing in Rome, has suggested reforms that the doctrinal congregation (CDF) could undertake if it wanted to:

-

Practice subsidiarity; don't deal with an issue that comes to Rome when it could be dealt with locally or regionally.

-

Honor the right of an accused to a fair hearing: the accused should be given the accusations in writing well beforehand, be present from the outset, be faced with the accuser(s), and be represented and accompanied by a professional of his/her choice.

-

The staff of the congregation should be "theologians of diverse schools."

-

They should have limited terms.

-

The congregation could publish the works of the International Theological Commission and the Pontifical Biblical Commission as its own. These commissions "have handled their sources more skillfully, argued their case more compellingly, and produced more convincing documents than those coming from the CDF itself."

-

In sum, the congregation could be "promoting theology that would be creatively faithful and pastorally effective in the multi-cultural and fast-changing world of today."

Gerald O'Collins, "Art of the possible," The Tablet [London] (14 July 2012).

See Vatican Council II (1962-1965)

Regency

The stages of Jesuit formation

After the first five years of study and formation, the regent devotes 2-3 years to full-time apostolic work (ministry) with supervision, often in a Jesuit high school, sometimes in a Jesuit university or other Jesuit ministry. In addition to the ministry provided, he thus also gains experience for reflection and integration in the next stage, theology.

See also Novitiate, First Studies, Theology and Tertianship

Regis, John Francis (1597-1640)

French Jesuit; home missioner; saint

After the devastation of religious war (Huguenots vs. Catholics), John Francis Regis ministered throughout southern France. "He consoled the disturbed of heart, visited prisons, collected food and clothing for the poor, established homes for [the rehabilitation of] prostitutes. . . . His influence reached all classes and brought about a lasting spiritual revival . . . . " (MacDonnell, Jesuit Family Album [Fairfield, CT: Clavius Group).

After the devastation of religious war (Huguenots vs. Catholics), John Francis Regis ministered throughout southern France. "He consoled the disturbed of heart, visited prisons, collected food and clothing for the poor, established homes for [the rehabilitation of] prostitutes. . . . His influence reached all classes and brought about a lasting spiritual revival . . . . " (MacDonnell, Jesuit Family Album [Fairfield, CT: Clavius Group).

Miraculous cures of the sick, attributed to his intercession, took place during his life and after his death.

Many institutions are named after him (e.g., the Jesuit university and high school in Denver and the high school in New York City).

Reinert, Paul (1910-2001)

American Jesuit; president of St. Louis University (1949-1974); leader in Catholic higher education and U.S. higher education in general

In addition to the usual Jesuit course of formation and education, Paul Reinert earned a doctorate in education from the University of Chicago (1944) and then went to St. Louis University as dean of the College of Arts and Sciences, soon became academic vice president, and a year later president. He was 39.

In addition to the usual Jesuit course of formation and education, Paul Reinert earned a doctorate in education from the University of Chicago (1944) and then went to St. Louis University as dean of the College of Arts and Sciences, soon became academic vice president, and a year later president. He was 39.

His 25-year tenure was remarkable in many ways: the admission to SLU, located in a former slave state, of the first African-American student; the revitalization of mid-town St. Louis to which he was heavily committed and in which he was highly involved; the academic advancement and broadening and deepening of the university into a major research institution; and the expansion and improvement of the campus in spite of difficult financial times. Perhaps his most important achievement was the pioneering change he brought in the 1960s, carefully and gradually, to the governance of the university: from Jesuit "ownership and control" to Jesuit "influence," with a separately incorporated Jesuit community; from an all-Jesuit administrator board of trustees to a board whose majority were lay people; and from an administration largely of Jesuits to one with a significant number of lay leaders.

His leadership beyond St. Louis and the university came to be recognized nationally; he served on presidential and other federal committees, was involved in every important national education association, and was awarded a good number of honorary degrees. In 1967 he brought all this experience to the gathering of 20 key presidents (like Theodore Hesburgh of Notre Dame) known as the Land O' Lakes Conference that played an important part in the articulation of a Catholic identity for Catholic universities.

Paul Reinert and Paul Shore, Seasons of Change: Reflections on a Half Century at St. Louis University (1996)

Anthony Dosen, Catholic Higher Education in the 1960s: Issues of Identity, Issues of Governance (Information Age Publishing, 2009), ch. 4: "St. Louis University: From Catholic Frontier College to Catholic Urban University"

Religion and Science Debate

Over the years I have taught an undergraduate course in science many times, some- times on my own and other times with colleagues from the Xavier University physics department, Terry Toepker and Marco Fatuzzo. Based on these teaching experiences, I am convinced that quite often there are sharp conflicts between theologians and scientists as a result of one side or the other cavalierly setting aside legitimate boundaries between the different academic disciplines. But there is no conflict between religion and science as such since they represent closely interrelated but still different dimensions of one and the same physical reality. For example, natural science in Western civilization has clearly benefited from antecedent religious belief in a rationally ordered world as a consequence of ongoing divine providence over the world. Most theologians, in turn, have relied on the best natural science of the day to explain the teachings of the church.

The perennial problem, however, is that the scientific understanding of physical reality keeps changing as a result of further research and empirical observation whereas many times theologians and church leaders tend to stay with a given scientific understanding of reality beyond the time that it is generally recognized as valid by the scientific community. One obvious example of this tendency was the condemnation of Galileo by the Vatican in 1633 largely because his empirically based observations were in conflict with the Aristotelian/Thomistic philosophy that church officials had followed for centuries. Likewise, in the late 1500s, when Galileo first proposed heliocentrism (the sun is the center of our system) as opposed to geocentrism (the earth is the center), he should have proposed it as a scientific hypothesis awaiting confirmation from further research and empirical verification. For only with the publication of Johannes Kepler's laws of planetary motion in 1609 and 1619 did the mathematics on which heliocentrism is based precisely match up with the empirical observations of Tycho Brahe on which Kepler so heavily relied in formulating those same laws.

JAB

Joseph A. Bracken, SJ, The World in the Trinity: Open-Ended Systems in Science and Religion (Minneapolis: Fortress, 2014)

Bracken, Subjectivity, Objectivity and Intersubjectivity: A New Paradigm for Religion and Science (Conshohocken, PA: Templeton 2009)

Religions, Non-Christian

One of the major accomplishments of the Second Vatican Council* (1962-1965) was a reversal of a centuries-long negative attitude toward non-Christian religions—Judaism especially, as well as Islam, Hinduism, Buddhism, and others. Even before the council, the Catholic Church had prepared the way for this reversal by condemning the long-held belief that there is no salvation outside the church. Now Vatican II went on to affirm that non-Christian religions contain truth and goodness and to call for Christian dialogue with members of these faiths on an equal and mutually respectful footing. The way to be religious, in our pluralist world, is to be "interreligious."

See "Inter-Religious Dialogue"

Religious Order/Religious Life

In Eastern Orthodox and Roman Catholic Christianity (less frequently in Anglican/Episcopal Christianity), a community of men or women bound together by the common profession, through "religious" vows, of "chastity" (better called voluntary "consecrated celibacy" [and thus not to be confused with the imposed celibacy of Roman Catholic clergy]), "poverty," and "obedience." As a way of trying to follow Jesus' example, the vows involve voluntary renunciation of things potentially good: marriage and sexual relations in the case of "consecrated celibacy," personal ownership and possessions in the case of "poverty," and one's own will and plans in the case of "obedience."

This renunciation is made, not for its own sake, but "for the sake of [God's] kingdom" (Matthew 19:12), as a prophetic witness against a culture's abuse of sex, wealth (greed), and power (domination) and toward a more available and universal love beyond family ties, personal possessions, and self-determination. As a concrete form of Christian faith and life, it emphasizes the relativity of all the goods of this earth in the face of the only absolute, God, and a life lived definitively with God beyond this world.

This way of life first appeared in the second half of the first century in the person of "virgins" (mostly women but also some men) who lived at home and, by refusing to marry and produce offspring (they claimed to be "spouses of Christ"), countered the absolutist claims of the state (Rome), and hence many of them became martyrs. After Constantine's conversion to Christianity (313) and Christianity's establishment as the state religion, "religious life" developed further as a major movement away from the "world" and the worldliness of the church. The monastic life of monks and nuns is a variation on this tradition. At the beginning of the modern Western world, various new religious orders sprang up (the largest being the Jesuits) that saw themselves not as fleeing from the world but as "apostles" sent out into the world in service. Some of these new communities were women's, but the church tried "sometimes even with persecution" to keep women within cloister.

Restoration of the Society of Jesus (1814)

Calendar year 2014 marked 200 years since the Restoration of the Society of Jesus following 41 years of Suppression. Pressured by the royal courts of Portugal, France, and Spain, Pope Clement XIV suppressed the Society, causing Jesuits throughout the world to lose their communities, ministries, and properties and often go into exile. Pope Pius VII, a Benedictine, restored the Society on August 7, 1814. The living spirit and tradition of the Society, however, could not readily be recovered. As historian John O'Malley has written, "the result [of the attempts to restore] was an often wooden, moralistic and legalistic interpretation of the normative texts. But the discrepancy between such interpretations and the way life had to be lived made itself felt ever more keenly."

Still, for the Society in the U.S, the hundred years after the Restoration was a time of new life, especially in the area of Jesuit education. Twenty-four of today's 27 American Jesuit colleges and universities were founded as were many of the high schools. (U.S. Jesuit schools, after the European model, originally covered six years, comprising the equivalent of today's high school and the first years of college).

See related information on the Suppression of the Society of Jesus

See brief videos on the Suppression and Restoration

Resource page for the Suppression and Restoration of the Society of Jesus

A directory of Jesuit Retreat Houses and Spirituality Programs throughout the world.

Review for Religious

A Journal

Published by the Missouri Province Jesuits from 1942 through January 2012, the collection documents the dramatic changes that took place in religious life over a span of 70 years. The journal published articles of interest for women and men religious across the spectrum of religious life, from active apostolic communities to contemplative monastic communities. Articles covered a range of topics pertinent to religious life, including prayer and spirituality, current best practices, and canonical guidelines.

Rhodes, Alexander (1591-1660)

French Jesuit; missioner to Vietnam

Alexander Rhodes, of Jewish Spanish descent, was born in Avignon in southern France. In 1625, as a Jesuit missioner, he went to Cochin, China, and two years later to Tonkin in Indochina. There he did gigantic work in building a church which through three and a half centuries of turbulent history . . . numbers those who have died for the faith in the hundreds of thousands, a record for protracted martyrdom with few, if any, parallels in the annals of Christianity. (Bangert, A History of the Society of Jesus (1968).

In his missiology, Rhodes favored an understanding and acceptance of Vietnamese customs, he wore Vietnamese clothing, and he was a master of their language, being the first person to transcribe it in western characters and write its grammar. He insisted on the development of a native clergy and arranged with Rome to have church officials unconnected to the Portuguese colonial system. He trained catechists who became the backbone of the young but fast-growing Vietnamese church.

See Phan, Mission and Catechesis: Alexandre de Rhodes and Inculturation in Seventeenth-Century Vietnam (1998).

Ricci, Matteo (1552-1610)

Italian Jesuit; missioner to China, pioneer practitioner of inculturation

First Jesuit to enter the forbidden kingdom of China and reach the court of the emperor; adopted Chinese language, dress, and culture, and wrote two of the great masterpieces of Chinese (Mandarin) literature.

First Jesuit to enter the forbidden kingdom of China and reach the court of the emperor; adopted Chinese language, dress, and culture, and wrote two of the great masterpieces of Chinese (Mandarin) literature.

Born the year Francis Xavier died, Ricci was the living incarnation of the adaptive principles set out by the Jesuit visitor Alessandro Valignano (1538-1606) in his missiology for the Far East. Trained in mathematics and the sciences under Christopher Clavius (1538-1612) at the Roman College, Ricci appealed to the natural curiosity of the educated Mandarin class in China by his exhibition of clocks, prisms, mathematical instruments, oil paintings, and maps of the world.

He ran into difficulty with certain traditional Chinese ritual practices in honor of ancestors and of Confucius. His final judgment was that these practices were more cultural and civic than religious and so should be allowed to converts. The issue remained in dispute till the 18th-century condemnation of the "Chinese Rites" by the Vatican. "See "Inculturation."

Matteo Ricci is one of the five Jesuits that Ronald Modras treats in his Ignatian Humanism (Loyola, 2004). Vincent Cronin was Ricci's first book-length biographer in English (The Wise Man from the West [Dutton, 1954]). A more recent biography is The Memory Palace of Matteo Ricci by Jonathan Spence (Viking, 1984).

Rodriguez, Alphonsus (1533-1617)

Spanish Jesuit brother; doorkeeper; saint

Alphonsus Rodriguez's father was a prosperous cloth merchant in Segovia. When Peter Faber, one of the closest companions of Ignatius of Loyola, came to town to preach and teach catechism, he stayed with the family and along with other ministries prepared Alphonsus for his first communion. Alphonsus went to a Jesuit school but did not finish because his father died suddenly. He helped his mother carry on and eventually took over the family business. At 27, he married Maria Suarez and the couple had three children. But their happy family life was interrupted by the deaths in quick succession of one, then another child, then his wife, and finally the only remaining child, leaving Alphonsus a lonely, grieving widower.

At approximately age 35, he sought entry into the Jesuit novitiate to become a priest. But he was refused, told that he was too old and lacked sufficient education and health. He went to Valencia to finish his studies and applied again, and again was turned down, until the provincial superior overruled the examiners' decision. Shortly after entering the novitiate as a Jesuit brother, he was sent to the Jesuit college in Palma on the island of Majorca off the coast of Spain in the Mediterranean. He wound up spending the rest of his life there. After holding a number of positions in his early years there, he was appointed doorkeeper; he welcomed visitors who came to see Jesuits or students, delivered messages, and offered counsel to many who sought his advice. Among them was the young Peter Claver, whom he encouraged to go to the South American missions, where he became a minister to the slaves brought from Africa to Cartagena (in present-day Colombia).

Although few knew the deep, intense mystical inner life with which he was graced, many sensed the holiness of the man. When Alphonsus was declared a saint in 1888, the Jesuit poet Gerard Manley Hopkins celebrated the event with a sonnet that concludes . . .

Yet God (that hews mountain and continent,

Earth, all, out; who, with trickling increment,

Veins violets and tall trees makes more and more)

Could crowd career with conquest while there went

Those years and years by of world without event

That in Majorca Alfonso watched the door.

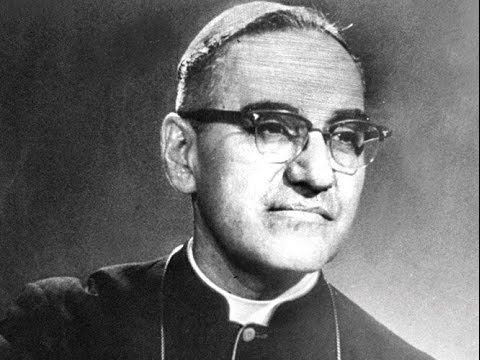

Romero, Oscar (1917-1980)

Archbishop of San Salvador; outspoken advocate for the oppressed Salvadoran people; martyr

When he was appointed archbishop in 1977, the reaction was mixed. He was thought to be "safe" by hierarchy aligned with the wealthy and powerful and by those in government and military oppressing the people and thought to be disappointing by those in favor of a church aligned with the poor, advocates of a Christian "liberation theology." He proceeded cautiously until his friend Rutillo Grande, SJ, was assassinated later that year. And then he did not cease to speak out against the violent repression of the poor majority. He wrote to U.S. President Carter asking him to stop funding the Salvadoran government and military because it was making the repression possible (the funding was continued), and he used his weekly Sunday radio broadcasts to make clear that the lower military had no right to obey orders to torture and kill. What he did pastorally for justice registered powerfully with Ignacio Ellacuria, leader of the Jesuits and lay people at the University of Central America (UCA), in their academic work to liberate the oppressed people of the country.

While celebrating Mass in a small hospital chapel on the evening of March 24, 1980, the archbishop was shot dead on orders from Roberto D'Aubuisson, founder of the right-wing ARENA party, who was never brought to justice.

Though Romero was esteemed as a martyr and saint by the people, his cause for canonization was blocked for decades by elements in the Vatican that, without foundation, considered his inspiration Marxist rather than Christian. Pope Francis "unblocked" his cause, declaring him a martyr of justice for the poor.

Jon Sobrino, Archbishop Romero: Memories and Reflections (Orbis Books, 2016)

Kevin Clarke, Oscar Romero: Love Must Out (Liturgical Press, 2015)

James R. Brockman, Romero: A Life (Orbis Books, 1989), an updated version of the biography that originally appeared in 1982.

Jon Sobrino, No Salvation Outside the Poor: Prophetic-Utopian Essays (Orbis Books, 2015).

Ruiz de Montoya, Antonio (1585-1652)

Peruvian Jesuit, Founder of "reductions" for indigenous people; student and scholar of their culture.

Tireless missionary among the indigenous peoples with whom he founded 13 reductions (protective communities), promoting their quality of life and defending this life from the increasing threats emanating from the Portuguese bandeirantes and the Spanish or creole traders in search of slaves and material wealth. An apostle, driven by an insatiable intellectual curiosity, which urged him to go beyond appearances to understand the territory in which he moved, its flora and fauna, recognizing cultural diversity and establishing intercultural ties.

Ruiz de Montoya went to the other, recognizing them as a brother or a sister, which explains why he learned the language and inserted himself in the Guarani culture, deepening his knowledge of nature, culture, people, and the experience of God on whom his life was anchored. His writings address various fields of knowledge: geography, biology, ethnology, grammar, and mystical theology.

The Jesuit university in Lima, Peru, is named after him.

JESUIT A TO Z: An expanded version of the publication "Do You Speak Ignatian?"