Terms: A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z

Terms B

- Ball, Teresa

- Barat, Madeleine Sophie

- Barry, William A.

- Bea, Augustin

- Beatification

- Bellarmine, Robert

- Bergoglio, Jorge

- Berrigan, Daniel

- Bible

- Billiart, Marie-Rose-Julie and

Blin de Bourdon, Françoise - Bishop

- Black Madonna

- Body of Christ

- Bolland, Jean

- Books

- Boscovich, Roger Joseph

- Brackley, Dean

- Brebeuf, John

- Buckley, Michael J.

Jesuit Terms B

Ball, Teresa (1794-1861)

Missioner and Educator

At a time when the Sisters of Loreto (formal title: Institute of the Blessed Virgin Mary) were forbidden by the church to acknowledge Mary Ward (1585-1645) as their founder, a remarkable religious woman, Dublin-born, very different in talents and temperament from Mary Ward, but imbued with her ideals — Teresa Ball — brought the Loreto spirit from York, northern England, to Dublin, Ireland (1821), from where it spread and brought its schools to India (1841), Canada (1847), Spain (1851), and elsewhere. "Today there are 150 Loreto schools and colleges around the world educating as many as 70,000 students in places like Sudan, Australia, Peru and Gibraltar as well as Ireland and the UK" (MacDonald, The Tablet).

These schools are all part of the "Loreto Education Trust," one of the world's best-known education networks (though not well known in the U.S.). The Trust works to maintain the schools' Catholic and Loreto "ethos" (the distinguishing character) even as the number of IBVM sisters is in decline. Enrolling students of diverse religions and none, their largely lay leaders insist that parents support the schools' ethos and they themselves try mightily to meet the students where they are and cater to their needs. "The charism continues because the staff in the schools carry it on" (Rionach Donlon, IBVM, chair of the Loreto Education Trust).

Sarah MacDonald, "On a mission to teach," The Tablet (21 May 2011).

"Portrait of Frances Ball before she entered the Bar Convent, York" from The Tablet (21 May 2011), 55.

Back to top

Barat, Madeleine Sophie (1779-1865)

Founder of the Society of the Sacred Heart

Madeleine-Sophie Barat was born in France in 1779 in the little Burgundian town of Joigny. She went to Paris in 1795, at the height of the French Revolution, and initially considered becoming a Carmelite. However, her experience of Revolutionary violence in Joigny and Paris led her on another path. In 1800 she founded the Society of the Sacred Heart whose purpose was to make known the love of God revealed in the Heart of Christ, and take part in the restoration of Christian life in France through the education of young women of the rich and the poor classes.

The Society of the Sacred Heart quickly expanded within Europe and beyond. At the same time Sophie Barat also grew, transformed by her experience as leader and friend to so many women who joined her. She learnt to face the impact of Jansenism within herself, her family, (especially in her brother Louis Barat, who became a Jesuit), and within the Church. Over many years and inner struggles Sophie Barat came to understand that the true counter-balance to Jansenism was the experience of the love of God revealed in the Heart of Christ.

Sophie Barat had a natural capacity for friendship and she enjoyed a broad network of relationships, with her family, with members of the Society, with the clergy, and with students and friends in all walks of life. On another level, Sophie Barat was awake to the social, political, economic and religious currents operating in Europe and in the wider world of her time. By her awareness of their impact on the world of education Sophie Barat ensured the Society's contribution to the education and the promotion of women in her time and into the future.

In exercising her role as founder and superior general Sophie Barat gradually created her own style of leadership. This tended towards moderation, seeking the middle ground, accepting the possible, more realistic option, rather than the impossible ideal; and she tended by instinct to consult rather than decree. This style of leadership was tested several times within and without the Society, especially from 1806-1815 and 1839-1851. In these periods of crisis the Fathers of the Faith, and after 1815 the Jesuits in France and Rome, were involved in the progress of the Society of the Sacred Heart, and particularly in the tensions surrounding Sophie Barat's leadership. Nevertheless, Sophie Barat remained the superior general of the Society of the Sacred Heart from 1806 until her death in 1865.

Sophie Barat's spiritual leadership of the Society was centered on the love of God revealed in the Heart of Christ. She was committed to a deep life of prayer and reflection, and she continually invited the members of the Society to see this as the basis for their inner lives and for whatever tasks they undertook. The importance of such qualities was stressed in the original Constitutions of the Society of the Sacred Heart of 1815 and reaffirmed in the revised Constitutions of 1982. They are also found consistently in the collection of Sophie Barat's 14,000 original letters and remain a vital legacy to the Society and to the wider Christian community.

By the time of her death in 1865 Sophie Barat guided an international community of 3,359 women, inspired by a deeply held spiritual ideal and offering a service of education to women in Europe, North Africa, North and South America.

No authentic portrait of Sophie Barat exists from her lifetime. She specifically refused to sit for a portrait, or to have her photograph taken.

Madeleine Sophie Barat was canonised a saint of the Roman Catholic Church on 25 May 1925.

For a discussion of the relations between Madeleine Sophie Barat and the Jesuits, see Phil Kilroy, The Society of the Sacred Heart in 19th century France (Cork University Press, 2012) pp. 133-166. Also Phil Kilroy, Madeleine Sophie Barat. A Life (Cork University Press, 2000/Paulist Press, 2000) passim.

Back to top

Barry, William A. (1930-2020)

American Jesuit; teacher and practitioner of Ignatian spirituality; writer

William A. Barry is well known for his teaching and writing on Ignatian spirituality. After earning a doctorate in clinical psychology from the University of Michigan, he cofounded the Center for Religious Development (Cambridge, MA) and authored experience-based essays on giving the Ignatian Spiritual Exercises (see Barry and Connolly, The Practice of Spiritual Direction [Seabury, 1971]). All told, he is author or coauthor of twenty books of practical Ignatian spirituality.

He taught at Weston Jesuit School of Theology, the University of Michigan, and Boston College and engaged in administrative work in the Society of Jesus. From 1988 to 1991 he was rector of the Jesuit Community at Boston College and on the board of trustees. From 1991 to 1997 he was provincial superior of the Jesuits of New England.

In his last years, he gave retreats and spiritual direction at the Campion Renewal Center in Weston, MA.

Back to top

Bea, Augustin (1881-1968)

German Jesuit; scripture scholar (Old Testament); ecumenist

Augustin Bea was one of several Jesuits influential in the founding of Sophia University in Tokyo in 1910. He was head of the Jesuit-sponsored Pontifical Biblical Institute in Rome from 1930 to 1949. In the 1940s and '50s, he was a major player in the official Catholic Church's turn away from biblical fundamentalism toward acceptance of critical historical biblical scholarship. A prominent theologian at Vatican II, he contributed significantly to the major document on Divine Revelation. After the council, he was made a bishop and cardinal and became the creator and first head of the Vatican Secretariat for Promoting Christian Unity.

Back to top

Beatification

“Beatification” is the third step in the process of becoming a saint in the Catholic Church. This step follows the stage of being a “Venerable Servant of God” and just before full “canonization” to sainthood. After being considered a Venerable Servant of God, the person is either declared to be a martyr for his or her faith by the Pope or proof of a miracle through the intercession of the person being considered for sainthood is validated. After this happens, the person is considered “beatified” (or “blessed”) and can be venerated at the local and regional level.

Bellarmine, Robert [in Italian Roberto Bellarmino] (1542-1621)

Italian Jesuit; eminent controversial theologian; preacher; cardinal; Saint

On his mother's side, Robert Bellarmine was the nephew of Pope Marcellus II. As a Jesuit, he was educated in theology at the University of Padua and then at Louvain in Belgium, where he joined the new Jesuit faculty. While there, he studied the writings of Luther and Calvin and taught theology by answering the reformers' objections to the Roman church. Later, when he was called to teach at the premier Jesuit-sponsored Roman College, he composed and published his three volumes of Controversies (1579, 1588, 1593), which went through twenty editions and were read by Catholics and Protestants alike. In 1598 he published his famous Catechism; it was translated into 62 languages.

On his mother's side, Robert Bellarmine was the nephew of Pope Marcellus II. As a Jesuit, he was educated in theology at the University of Padua and then at Louvain in Belgium, where he joined the new Jesuit faculty. While there, he studied the writings of Luther and Calvin and taught theology by answering the reformers' objections to the Roman church. Later, when he was called to teach at the premier Jesuit-sponsored Roman College, he composed and published his three volumes of Controversies (1579, 1588, 1593), which went through twenty editions and were read by Catholics and Protestants alike. In 1598 he published his famous Catechism; it was translated into 62 languages.

Already a theological advisor to the pope, he was next made a cardinal (1599) over his own and the Jesuit superior general's objections. Pope Clement VIII decided the matter: "We elect this man because he has not his equal for learning in the Church of God." Bellarmine turned around and presented the pope with a denunciation of the major abuses in the pope's own Roman headquarters. In his own personal life, he lived simply and cared for the poor. Yet, because of his cardinal role, he had to put up with wearing the red robes, being surrounded by servants, and having carriages to transport him. As a cardinal, he was also a voting member of the conclaves that elected Leo XI (1605), and six weeks later Paul V.

For years Bellarmine had asked to retire but was told again and again that he was indispensable. Then in 1621, at the age of 79, he was finally allowed to have his wish; he moved to the Jesuit novitiate and died there a few weeks later.

Back to top

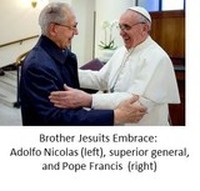

Bergoglio, Jorge Mario (Pope Francis) (1936- )

Argentinian Jesuit, provincial, cardinal, first pope from the Society of Jesus

On March 13, 2013, Argentina's Cardinal Jorge Bergoglio was elected the 266th leader of the Roman Catholic Church with its 1.2 billion members. He took the name Francis after St. Francis of Assisi, who lived in poverty and simplicity and was a champion of the poor.

On March 13, 2013, Argentina's Cardinal Jorge Bergoglio was elected the 266th leader of the Roman Catholic Church with its 1.2 billion members. He took the name Francis after St. Francis of Assisi, who lived in poverty and simplicity and was a champion of the poor.

Although he was said to have had the second highest number of votes in each of the four ballots of the 2005 conclave that elected Josef Ratzinger Pope Benedict XVI, Cardinal Bergoglio was by no means considered the front runner going into the conclave of 115 cardinals from 48 countries that would elect him on the first full day of voting (5th ballot).

It was a historic act by the cardinals—the first non—European pope in 1200 years. "[Now] the global outlook of the church is reflected at the highest level of the church," said Agbonkhianmeghe Orobator [accent on the second syllable], the Jesuit provincial superior in East Africa and a distinguished theologian. "I want to believe that considering the humble and down-to-earth background of Pope Francis . . . the church is in good hands—not just the pope's alone, but the hands of the entire people of God across the globe" (ncronline).

Jorge Bergoglio was born in Buenos Aires in 1936 to Italian immigrant parents. His father was a bookkeeper with a local accounting firm (The Tablet [April 13, 2013]). After earning two degrees in chemistry, he chose a different path and entered the Jesuit novitiate in 1958. Following initial Jesuit formation and study in the humanities, he taught literature and psychology for several years. He studied theology in Buenos Aires and was ordained a priest in 1969. He served as master of novices from 1971 to 1973, when, at the age of 36, he was appointed provincial.

Read more on Jorge Bergoglio here.

Back to top

Berrigan, Daniel (1921-2016 )

American Jesuit; anti-war activist; poet

Daniel Berrigan grew up with his five brothers in a family where "violence [was] a norm of existence." His father, "an incendiary without a cause" (Berrigan's autobiography) was hard on the boys and harder still on their mother. Even though he blamed the church for enabling the mistreatment of his mother, he felt a call to priesthood and religious life and entered the Jesuits right out of high school. His younger brother Philip, a Josephite (multiracial Catholic religious congregation devoted to serving African Americans), had perhaps the greatest influence on his life. They marched together at Selma in 1965, and they protested U.S. military involvement in Vietnam. With seven others, they destroyed draft files at Catonsville, MD, in 1968—a symbolic act of non-violent resistance to the law for which they were all sentenced to prison (see his play The Trial of the Catonsville Nine). After hiding out when he was supposed to begin serving his term, he was finally caught and served two years. Subsequently, for other anti-war acts against other wars, he served a total of seven years.

Daniel Berrigan grew up with his five brothers in a family where "violence [was] a norm of existence." His father, "an incendiary without a cause" (Berrigan's autobiography) was hard on the boys and harder still on their mother. Even though he blamed the church for enabling the mistreatment of his mother, he felt a call to priesthood and religious life and entered the Jesuits right out of high school. His younger brother Philip, a Josephite (multiracial Catholic religious congregation devoted to serving African Americans), had perhaps the greatest influence on his life. They marched together at Selma in 1965, and they protested U.S. military involvement in Vietnam. With seven others, they destroyed draft files at Catonsville, MD, in 1968—a symbolic act of non-violent resistance to the law for which they were all sentenced to prison (see his play The Trial of the Catonsville Nine). After hiding out when he was supposed to begin serving his term, he was finally caught and served two years. Subsequently, for other anti-war acts against other wars, he served a total of seven years.

After the Vietnam War ended, they turned their attention toward nuclear weapons. Together with six colleagues they entered the General Electric plant in King of Prussia, PA, and hammered on nuclear weapon nosecones, inspired by the prophet Isaiah: "They shall beat their swords into ploughshares and their spears into pruning hooks; nation shall not lift up sword against nation, nor shall they learn war anymore."

"Dan loved his Church, his Jesuit community, he even loved America—but there is much in all three zones that is outrageous, and Dan was never able to be silent or passive about betrayals. This could have made him a ranter but the artistic side of Dan always found ways to channel his outrage into one or another form of creativity, whether via poetry or a wide variety of acts of witness" (Jim Forest).

Among his fifty books were fifteen volumes of poetry as well as autobiography, commentaries on the Old Testament prophets, and indictments of the established order, both secular and ecclesiastic (N.Y. Times). His writings reflect his deep commitment to social, political, and economic change in American society (Britannica Online). By themselves, apart from his activism, they would merit attention and admiration.

Daniel Berrigan: Essential Writings, Selected with an Introduction by John Dear (Maryknoll, NY: Orbis, 2009).

Back to top

Bible

From the Greek word biblia, meaning books, the Christian Holy Bible is a collection of scripture, including the sacred writings of the Old Testament (the Hebrew Bible), containing 39 books, and the New Testament, containing 27 books. When the early Judeo-Christian writings were bound together, they were called bibles.

Ignatius Loyola's Spiritual Exercises reflects the relationship he had with the Bible. Through the scriptures and imagination, he guided himself and others to greater faith, love, and understanding.

For more information see Ignatius and the Bible by John Padberg, SJ

For a number of Christian Bible translations in numerous languages, see here.

See the Qur'an, the Muslim Bible. The word qu'ran means "recitation" and indicates a strong preference for chanting rather than just reading it. It contains 114 suras ("chapters"), each with a varying number of verses. Of interest to Christians, sura 19 tells of Maryam (Mary) and her son Isa (Jesus), an important Muslim Prophet [w. 16-37].

Back to top

Billiart, Marie-Rose-Julie (1751-1816) and Marie-Louise-Fran çoise Blin de Bourdon (1756-1838)

Co-Founders of the Sisters of Notre Dame de Namur

In October of 1794, in Amiens, France, Julie Billiart and Françoise Blin de Bourdon met for the first time and, because they recognized the inherent goodness in one another, began an unlikely friendship. By this time, both women had been tested by sufferings endured during the height of the French Revolution. Julie, a daughter of the merchant class from the small village of Cuvilly, had also suffered twenty-two years of physical infirmity and the psychological stresses brought on by family trials. Françoise had been tested by the deaths of her mother and beloved grandparents and by a period of terrifying imprisonment which she shared with her family and other members of the French aristocracy prior to the fall of Robespierre.

Although from widely varied social classes, both Julie and Françoise had an inclination for the spiritual and a deep inner life. Both had been attracted to the contemplative order of Carmelites and both had emerged from their sufferings more faith-filled and committed. A small group of devout women began to gather around Julie's sickbed in rented lodgings within the Blin family town home. Père Antoine Thomas (1753-1833), a Father of the Faith, an order founded in Rome with the intention of resurrecting the Society of Jesus (that had been suppressed by order of the pope in 1773), and, as of 1814 (when the Jesuits were reestablished), a Jesuit, was in hiding in Amiens because he had refused to take the constitutional oath. He was a teacher at the Sorbonne, known for his erudition as well as his virtue and became spiritual adviser to Julie, Françoise and the others.

Gradually, in Amiens and the surrounding area, the little group of women in the rue des Augustins received high commendations for their care of the poor, their kindness toward the sick and the suffering, their unique ability to instruct the catechism and to prepare young and old for the reception of the sacraments. In the fall of 1801, the Fathers of the Faith opened a secondary school for boys in Amiens and Father Varin (1769-1850), the superior and a friend of Father Thomas, began to persist in his effort to have Julie found a new congregation and enjoined upon her the duty of praying for subjects for this new institute. France was in dire need of educators in the aftermath of the Revolution. Though the voice of reason questioned the viability of this course of action given Julie's still paralyzed state, Julie and Françoise did as Father Varin bid and asked the Carmleites of Amiens to pray with them.

From the outset, and like so many women in the more than 250 years since the founding of the Society of Jesus in 1540, Julie and Françoise saw the possibilities in a religious congregation free to move beyond the constraints of the cloister and to go wherever needed, one that would extend beyond diocesan boundaries and whose communities of religious women educators would be united by regular communication with a Mother General. Together they faced the hostility of an ecclesiastical hierarchy reluctant to permit these freedoms to women and, subsequent to persistent misunderstandings with the bishop and clergy in Amiens, they relocated the motherhouse to Namur, Belgium, which was at the time a part of Napoleon's French empire, in response to the invitation of the bishop there.

Since its official founding in 1804, the Sisters of Notre Dame de Namur have established schools and engaged in a variety of ministries on five of the world's seven continents, always from an educational perspective and with a preference for poor women and children. Documents to further the process of canonization were prepared for both Julie and Françoise during the latter part of the nineteenth century and Julie's cause was submitted first since hers was founding spirit and charism, that of recognizing everywhere, at all times, and in all persons and things the infinite goodness of God. "Ah! Quil est bon, le bon Dieu!?" In 1969, Julie, who had taken as her religious name, Soeur Ignace, was canonized a saint of the Catholic Church.

Bishop / Episcopacy

The word bishop comes from the Old English biscop and ultimately from the New Testament Greek episkopos meaning "overseer." (In the first Christian centuries, the role of episkopos was not clearly differentiated from that of presbyteros ("elder" or today "priest.")

Within many branches of Christianity, the bishop is a consecrated member of the clergy given authority and oversight—often for a geographical area called a diocese. In contemporary Catholicism, bishops are appointed by the pope, but for many centuries, they were locally chosen. The first Catholic bishop of the U.S., John Carroll, was elected by his fellow clergy.

In the line of succession from Jesus' apostles (the claim is disputed), bishops are said to possess the fullness of the "ministerial" priesthood that has three grades—deacon, priest, and bishop (in contrast to the "priesthood of the faithful")—and thus to have the power to ordain priests and other bishops.

According to the Second Vatican Council, the full body of bishops—the episcopacy—bears the responsibility for the governance of the entire church (in union with the bishop of Rome [the pope] in Roman Catholicism. Regional groups of bishops (as, for example, the U.S. episcopacy) were given relative autonomy and power by the council, but over the past 30 years the Vatican has largely curtailed that.

Back to top

Black Madonna

See "Montserrat, Our Lady of"

Back to top

Body of Christ

See "Incarnation"

Back to top

Bolland, Jean (1596-1665)

Belgian Jesuit after whom the Society of Bollandists is named

Jean Bolland was a theologian-historian and early leader of the association of critical hagiographical scholars after whom it was named—the Bollandists. The work was started in 1603 by the Dutch Jesuit Heribert Rosweyde, who was engaged in producing critical editions of the enormous number of manuscript lives of the saints in the libraries of northern Europe. His proposed grand work, sent to the distinguished Jesuit theologian Robert Bellarmine, drew the following response: "This man, then, counts on living two hundred years longer!" Bolland brought new energy and direction to the work, modifying his predecessor's plan but still greatly underestimating what it would take to realize it.

The first two volumes of the Acta Sanctorum (starting with January in the church calendar) appeared in 1643, the collaborative work of Bolland and his new assistant Godfrey Henschen (1601-1681), who surpassed his former teacher in the quality and method of his scholarship and set the standard for the volumes to come. In 1659 a third Jesuit joined the team, Daniel van Papebroch (1628-1714), also a gifted student of Bolland. Scholars from all over Europe, enthusiastically helping the great work, sent the team manuscripts. And the two younger Jesuit scholars went on a long and successful manuscript-gathering tour of Western Europe.

Not everybody was enthusiastic about the project, however. The volumes, as they came out, stirred angry responses from individuals and a whole religious order because of its critical separating of fact from legend. Papebroch bore the brunt of the outrage.

The Bollandist Society suffered various losses after the suppression of the Jesuits in 1773, but was re-established and moved from Antwerp to Brussels in the 1840s. Still at work today in their superb library—one of the best in Europe—the Bollandists, now including non-Jesuit scholars, have produced more than 120 volumes on the saints. Their great service to the church has been to present as honest and clear a picture of the lives of saints, people considered worthy of veneration and imitation, as critical historical scholarship can yield.

Visit the Bollandist Society website.

See Hippolyte Delehaye, The Work of the Bollandists through Three Centuries, 1615-1915 (Princeton Univ. Press, 1922).

Back to top

Books

Foundational Readings

Ignatius of Loyola: Spiritual Exercises and Selected Works

Ignatius of Loyola: Spiritual Exercises and Selected Works

George Ganss, S.J., Ed., 1991- A Pilgrim's Journey: The Autobiography of Ignatius of Loyola

Joseph N. Tylenda, S.J., translator, 1991 - Finding God in All Things: A Companion to the Spiritual Exercises

William A. Barry, S.J., 1991 - The First Jesuits

John W. O'Malley, S.J., 1993 - Draw Me Into Your Friendship: A Literal Translation and a Contemporary Reading of the Spiritual Exercises

David Fleming, S.J., 1996 - Heroic Leadership: Best Practices from a 450-Year Old Company That Changed the World

Chris Lowney, 2003

- Ignatian Humanism: A Dynamic Spirituality for the 21st Century

Ronald Modras, 2004 - An Ignatian Spirituality Reader

George Traub, S.J., 2008 - A Jesuit Education Reader

George Traub, S.J., 2008 - The Joy of the Gospel (Evangelii Gaudium)

Pope Francis, 2013 - The Jesuits: A History from Ignatius to the Present

John W. O'Malley, S.J., 2014 - Ignatius of Loyola: Legend and Reality

Pierre Emonet, S.J., 2016

Associated With Xavier University

- Teresa of Avila and the Politics of Sanctity

Gillian T. W. Ahlgren, Theology Department, 1998

Gillian T. W. Ahlgren, Theology Department, 1998 - Faith and Action: A History of the Catholic Diocese of Cincinnati, 1821-1996

Roger Fortin, Provost and Academic Vice President, 2002 - The Language of Battered Women: A Rhetorical Analysis of Personal Theologies

Carol Winkelmann, English Department, 2003 - Into the Abyss of Suffering

Kenneth Overberg, S.J., Theolgy Department, 2003 - Through the Year with Oscar Romero

Irene Hodgson, Translations, Modern Languages Department, 2005 - Spirituality in the Mother Zone: Staying Centered Finding God

Trudelle Thomas, English Department, 2005 - Conscience in Conflict, 3d ed.

Kenneth Overberg, S.J., Theology Department, 2003 - To See Great Wonders: A History of Xavier University

Roger Fortin, Provost and Academic Vice President, 2006 - Christianity and Process Thought: Spirituality for a Changing World

Joseph Bracken, S.J, Theology Department, 2006 - Alice in Academe and Other Stories

Joseph Wessling; emeritus, English Department, Illustrated by Holly Shapker, Art Department, 2006 - A Concise Guide to the Documents of Vatican II

Edward P. Hahnenberg, Theology Department, 2007 - Xavier University: A Celebration of Art - A Tribute to the 175th Anniversary of Xavier

Kittie Uetz and Jenny Shives, Art Department, 2007 - Hope Sings, So Beautiful: Graced Encounters Across the Color Line

Christopher Pramuk, Theology Department, 2013

Back to top

Boscovich, Roger Joseph [in Croatian, Rudger Josip Boskovic] (1711-1787)

Croatian Jesuit; fearless, independent thinker; creative scientist; proponent of an early atomic theory of matter

A native of Ragusa (now Dubrovnik) in Dalmatia, the young Roger Joseph Boscovich was praised by one of his distinguished teachers: "He starts where I leave off." He taught at the Jesuit Roman College for 20 years (1740-1760). He published some sixty books and pamphlets on scientific subjects. In 1758, after years of reflection, he published his masterwork, A Theory of Natural Philosophy, anticipating much later findings of atomic physics. "From an absolutely new point of departure in physics, he conceived the material world as made up of individual non-extended points which are centers of action, while the action, be it attractive or repulsive, between the points is a function of the distance which separates them" (Bangert, A History of the Society of Jesus [1986]).

A native of Ragusa (now Dubrovnik) in Dalmatia, the young Roger Joseph Boscovich was praised by one of his distinguished teachers: "He starts where I leave off." He taught at the Jesuit Roman College for 20 years (1740-1760). He published some sixty books and pamphlets on scientific subjects. In 1758, after years of reflection, he published his masterwork, A Theory of Natural Philosophy, anticipating much later findings of atomic physics. "From an absolutely new point of departure in physics, he conceived the material world as made up of individual non-extended points which are centers of action, while the action, be it attractive or repulsive, between the points is a function of the distance which separates them" (Bangert, A History of the Society of Jesus [1986]).

He could be acerbic and did not suffer fools lightly. He judged that the famous Jesuit College Louis-le-Grand in Paris did not have up-to-date scientific instruments and criticized the blindness of Jesuits who considered Newton a heretic. The naïve rector of the Jesuit college at Sens, who showed him among the school's precious holdings a piece of Aaron's rod and a rib of the prophet Isaiah, was told, in the interest of truth, to throw them away. Boscovich more than any other 18th-century Jesuit thinker was responsible for defeating the attitude that Jesuits were closed to new ideas.

In the last 50 years or so, appreciation of Boscovich's work has grown considerably. The University of California, Berkeley, purchased a large collection of manuscripts and letters that now constitute the Boscovich Archives in its Bancroft Rare Books Library. And historians of science have honored him with books and articles and international symposia.

See Hill, 'Biographical Essay' in Roger Joseph Boscovich: Studies of His life and Work on the 250th Anniversary of His Birth, ed. Lancelot Law Whyte (1961).

Back to top

Brackley, Dean (1946-2011)

American Jesuit; volunteer to El Salvador after the murder of six Jesuits (1989)

After earning a doctorate in religious social ethics from the University of Chicago Divinity School, Dean Brackley worked in troubled neighborhoods in lower Manhattan and the South Bronx and taught at Fordham University for some nine years. One of his best-known writings draws on these years of ministry: "Downward Mobility: Social Implications of St. Ignatius' Two Standards" (Studies in the Spirituality of Jesuits [January 1988]).

In November 1989, six Jesuits at the University of Central America (UCA) in San Salvador (along with the housekeeper/cook from a nearby Jesuit seminary and her daughter who had sought refuge in the UCA Jesuit residence) were murdered—shot in the back of the head at close range to blow their brains out—by government forces (most of them trained at the School of the Americas in Columbus, GA). Brackley volunteered to help replace them. He then spent most of the last 21 years of his life (until he died at 65 of pancreatic cancer) teaching and doing administration at the UCA, writing, and ministering with a community of the poor. He was a frequent guide for North American and European visitors to Salvador, whether they came as learners or as pilgrims. He also visited various (Jesuit) universities in the U.S., delivering his vision of what a Catholic (and therefore Jesuit) university should be.

His contemporary presentation of Ignatian spirituality and the Exercises, equipping them for the "historical reality" of our time—The Call to Discernment in Troubled Times (Crossroad, 2004)—has already become a modern classic.

Brebeuf, John de [in French, Jean de Brébeuf] (1593-1649)

French Jesuit; missioner to New France

Though early in his Jesuit life he was beset by illness, John de Brebeuf became legendary for his strength and endurance and heroic in his gruesome torture and death. He was declared a saint in 1930.

He was in the second group of Jesuit missioners to go from their homeland to New France (1625), and he served there in two periods until he was put to death by the Mohawk in 1649.

Brebeuf was a leader of the illustrious but tragically short-lived mission to the Wendat (formerly called Huron) numbering some 30,000 in 20 villages. It was his determination to live among the people and to honor their culture and customs—not an easy thing to do. In one of his letters home to France, he wrote: "You may have been a famous professor or theologian in France, but here you will merely be a student and with what teachers! The Huron language will be your Aristotle and, clever man that you are, speaking glibly among the learned, you must make up your mind to be mute in the company of these natives."

In another letter home, Brebeuf described a native game in which players used a curved stick that he named "La crosse" because it reminded him of a bishop's crosier. To this day, the game bears that name.

The dream of the mission was to have the Wendat and the Europeans living together in harmony where the rites and tradition of both peoples could be strengthened and enriched by the values of the gospel. And gradually that dream came toward realization with the building of the settlement-compound Sainte-Marie that at its peak housed 23 Jesuits and 23 French lay volunteers along with the Wendat converts. But in 1648-49, repeated attacks by the Mohawk destroyed one village after another and killed most of the Jesuit and lay leadership, including Christian Wendat who had come to assume an important role in the blended community.

Brebeuf and his companions are memorialized in a long epic poem by Canadian poet E. J. Pratt, Brebeuf and His Brethren (1940). A less heroic but compelling portrait of a French Jesuit missioner to New France is painted by Irish-Canadian-American novelist Brian Moore in Black Robe (1985). The film version (1991), by Australian director Bruce Beresford with a screenplay by Moore, dramatizes the impossibility of the two cultures—French and aboriginal—ever coming together. Although the works make good fiction and good film, they are not historically accurate. In spite of great difficulty, the two cultures did come together and, indeed, lived together in a Wendat-French Christian community.

A reliable and clarifying essay on "The Jesuits in New France" by Jacques Monet appears in the Cambridge Companion to the Jesuits, ed. Thomas Worcester (2008).

Buckley, Michael J. (1931-2019)

American Jesuit; philosophical theologian; writer

Michael Buckley was for 14 years a part of the theological faculty at Boston College, during which time he served as the director of the Jesuit Institute and as Canisius Professor of Theology. Previously, he was a member of the Pontifical Faculty of Theology at the Jesuit School of Theology at Berkeley. He held various university positions, including visiting fellow at Cambridge University's Clare Hall, of which he was also a life member; he was also a professor of theology at Santa Clara University.

Michael Buckley was for 14 years a part of the theological faculty at Boston College, during which time he served as the director of the Jesuit Institute and as Canisius Professor of Theology. Previously, he was a member of the Pontifical Faculty of Theology at the Jesuit School of Theology at Berkeley. He held various university positions, including visiting fellow at Cambridge University's Clare Hall, of which he was also a life member; he was also a professor of theology at Santa Clara University.

Buckley was the author of numerous articles in systematic theology, philosophy, spirituality, science and theology, and the history of ideas. Among his books are: The Catholic University as Promise and Project: Reflections in a Jesuit Idiom (1998) and most recently Denying and Disclosing God: The Ambiguous Progress of Modern Atheism (2004).

He served as the president of the Catholic Theological Society of America, was a trustee for a number of universities and for Theological Studies, and participated on various boards and commissions.

Buckley received his BA and MA from Gonzaga University, his STM from Santa Clara University, and his PhD from the University of Chicago. He received two doctorates honoris causa and has also been honored with a Festschrift (Finding God in All Things: Essays in Honor of Michael J. Buckley, S.J., eds. Michael J. Himes and Stephen J. Pope [1996]).

JESUIT A TO Z: An expanded version of the publication "Do You Speak Ignatian?"