Mary, the Hidden Catalyst:

Reflections from an Ignatian Pilgrimage to Spain and Rome

Margo J. Heydt, Associate Professor, Social Work Department

Sarah J. Melcher, Associate Professor, Department of Theology

Xavier University

May, 2008

In the summer of 2006, we two colleagues from Xavier University undertook a ten day Ignatian pilgrimage along with several other Jesuit university colleagues (coordinated by the College of the Holy Cross). Our intention, when we began our journey, was to write from a feminist perspective about our experiences in learning about the history of a religious order of men. That fall, Dr. Heydt presented our initial reflections at the conference, Jesuit and Feminist Education: Trans-formative Discourses for Teaching and Learning, convened at Fairfield University. The development of a portion of the original presentation paper follows. It is illustrated by photographs, postcard pictures, and photographic slides from a Diorama taken and selected by Dr. Heydt and used in the PowerPoint of the conference presentation.1

Loyola Family Castle in Loyola, Spain

The pilgrimage retraced the steps of the early Jesuits, visiting important Ignatian sites in Spain and Rome. It spanned the lifetime of Ignatius of Loyola, from his birth in 1491 at the Loyola family castle to his death at age 65 (in 1556) in his simple apartment next to the Gesù, the church of the Society of Jesus in Rome. Our goal was to discover how women fit into the history of the early Jesuits to which we would be exposed. We thought that the focus would arise from the holes in the story the places where women should have been found, but were missing. What we encountered on the pilgrimage, however, differed from that in the following two dimensions. First, we share with you our surprise and delight at discovering how significant the influence of Mary, the mother of Jesus, was in the transformation of Ignatius of Loyola from a Spanish soldier of nobility to the spiritual founder of the Jesuits. Second, along the pilgrimage path, we were delighted to find that representations of women were considerably more abundant in European settings than what is typically found (in our experiences) in the United States. This was particularly true of the religious sites we visited in Spain. Not only were these representations more numerous, but most were also qualitatively different. We became fascinated by differences observed in the images of Mary found in Spain as contrasted with those more commonly seen in the U.S.A. and will discuss this dimension of our observations first. Before you continue reading, we invite you to pause for a moment and close your eyes to see what image of Mary comes to mind for you. In unofficial queries of others both during our trip and afterwards, a common icon of Mary that comes to mind for many is of a solemn light skinned bust with downcast eyes surrounded by folds of flowing blue and white fabric. For some, a simple gold halo floats above her head. If the image is full bodied, the woman would usually be a full length version of that same bust. Often she would be seated, and holding a barely visible infant well-wrapped in more blue and white fabric. For both Mary and the baby Jesus, there is no visible hair, no eye contact, and no hint of activity.

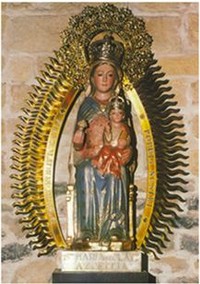

Santa Maria de Olatz: Santuario de Loyola

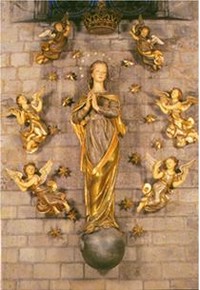

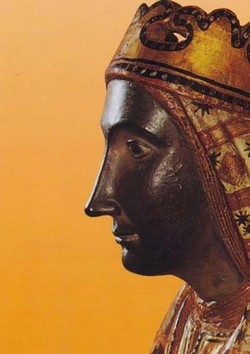

In contrast to this conventional Mary icon, the representations we encountered in Spain and Rome were quite varied. Eye contact was common in that the eyes of the sculpture or painting appeared to be looking at the viewer or at other figures in the artwork itself. Oftentimes, the figure's hair would be visible. In addition, the representation was more likely to be full-bodied and/or standing.

The figure's arms and/or hands were often raised or engaged in some kind of activity rather than folded or used only to hold the baby. The Jesus images in Spain and Rome also seemed to have eye contact with the viewer and showed Jesus at various stages of childhood instead of as a perpetual infant. Crowns of many styles worn by both Mary and Jesus tended to be large and ornate. For some images, there was both a crown and a halo. A wide range of colors was present in skin tones and fabrics for both Mary and Jesus. There was even a baby Jesus in pink! Most significantly, these empowering representations tended to portray a woman as agent, very much engaged with and affecting those around her. This was especially true of the statue of Mary in the Basilica of Mary Major in Rome where Mary appears to be blessing her audience while holding a squirming Jesus as a toddler.

Purisma Concepcion Basilica

de Santa Maria del Mar, Barcelona

Basilica of Mary Major, Rome Mary and Jesus at Xavier Castle

Ignatius had his conversion vision of Mary in

this Hospital near the family castle in Loyola.

Along with noting these many details about the representations of Mary and Jesus, the other dimension of our observations, the extent of Mary's influence on Ignatius of Loyola, also became increasingly evident. From the very first pilgrimage stop at the hospital where Ignatius was treated for his war wounds, we were amazed to hear and see displays that told the story of his vision of Mary while he was hospitalized. Upon visiting the Loyola family castle, a Diorama (a collection of small sculptures arranged in 26 vignettes) illustrated the major events of Ignatius life. Almost immediately, we were struck by how prominently Ignatius devotional relationship to Mary was portrayed throughout the vignettes. Later, however, what stood out to us was the minimal emphasis given in most Jesuit history accounts to this secret in the life of Ignatius. Dr. Heydt was able to obtain photographic slides of the Diorama and a copy of the accompanying text, in French, which Dr. Melcher laboriously translated. The vignettes demonstrated and the narrative described how images of the Madonna inspired Ignatius initial conversion experience. The continued appearance of such images was instrumental in confirming Ignatius decisions along his lengthy spiritual path. The Diorama clearly depicted that Ignatius became devoted to Mary, imploring her throughout his lifetime to help him be more like her son, Jesus. In addition to the story of the Diorama at Loyola castle, numerous other sites along the pilgrimage path emphasized the spiritual connections that Ignatius experienced with Mary and how pivotal these were in his turning away from a previous lifestyle, in his spiritual growth along this new path, and in his founding of the Society of Jesus. A brief enumeration of significant Marian visions, spiritual inspiration sparked by a painting or statue of Mary, and other kinds of Marian connections in Ignatius? life includes the following:

1. Marian influence in Ignatius early life at or near the Loyola estate.

2. Particular impact of his sister-in-law's (Magdalena Araoz's) painting of Mary hanging in the family castle.

3. Premier vigil of conversion before an image of Mary in Aranzazu where Ignatius pledges to live his life like Jesus.

4. Ignatius seriously considers murdering a Muslim who questions Mary's virginity, in order to defend her honor.

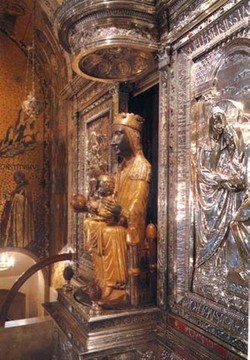

5. After a three day vigil, Ignatius lays down his sword in front of the Black Madonna at Montserrat, to take up the life of a religious.

6. Strong influence of Mary at Manresa while Ignatius meditates and writes the Spiritual Exercises in the cave.

7. Ignatius vision of Mary in the hospital of the Magdalena at Azpeitia.

8. He takes vows with some companions in front of the Mary statue at St. Paul's Outside the Walls Basilica in Rome.

9. Painting of Mary and Jesus prominent in Ignatius simple apartment in Rome.

10. Church of Santa Maria della Strada, the first church ever held by the Jesuits and the site of the future Gesù in Rome.

11. The Gesù itself called Our Lady of the Way Church

Ignatius' Apartment, Rome

As James W. Reitz explains it, Mary's prominent role in Ignatius life began with the wedding gift of a painting of Mary from Queen Isabella the Catholic to Magdalena, who had been her lady-inwaiting.2 Young Ignatius had contemplated this painting which played a role in his conversion.3 According to the Diorama text, Ignatius first considered following a spiritual path after reading about the lives of saints in books that were given to him by his sister-in-law, Magdalena, during his convalescence from his war wounds. He formed an idea of living out his life in the land of Jesus, afflicting himself with penances more severe than those endured by the saints. Ignatius felt that this general plan had been confirmed by a vision he had one night of the Madonna with the infant Jesus in her arms, a vision that filled him with immense joy: being awake one night, he saw clearly a likeness of Our Lady with the Holy Child Jesus, at the sight of which, for an appreciable time, he received a very extraordinary consolation.4

Vision of Mary (diorama)

1521

Recuperating from war wound

"He saw clearly a likeness of Our Lady with the Holy Child Jesus... (from which) he received a very extraordinary consolation."

The Loyola Castle Diorama text relates how the devotion of Ignatius to Mary continued. After leaving the Loyola castle to make his way to Jerusalem and the land of Jesus, the first stop Ignatius made was at Aranzazu, a Marian sanctuary in the village of Oñate. There Ignatius hoped to gain greater strength for his journey to Jerusalem through a vigil held before a statue of Mary.5 The Diorama text describes this as Ignatius? premier vigil of conversion, during which he pledged himself before an image of Mary to live his life like Jesus. In a letter written much later (1554), after the sanctuary at Aranzazu was damaged by fire, Ignatius describes how much his experience in the chapel there had meant to him.

Indeed, the fire was a great pity and misfortune, especially for those of us who are acquainted with the devotion which flourished there and the great service rendered to God our Lord. Whatever measures are necessary for the restoration of the monastery should be undertaken with much devotion. I may say I have a particular and personal reason for desiring it. When God our Lord granted me the grace to make some change in my life, I remember having received some benefit for my soul while watching one night in that church.6

The Diorama and other sources inform us that Ignatius continued his journey to Jerusalem. On the road to his next stop in Montserrat, Ignatius seriously disagreed with a Muslim who questioned the virginity of Mary. After the encounter, Ignatius apparently experienced an intense internal battle, feeling that he had not done his duty toward Mary.7 In reconsidering the disagreement, Ignatius felt that he should have defended Mary's honor more devotedly and contemplated catching up with the man to kill him. In the end, however, he headed in another direction, one literally determined by the mule on which he was riding, and he left the Muslim alone.

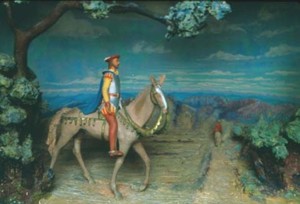

Defending Mary's Honor (diorama)

Meeting a Muslim, traveling on their mules montserrat.

The Muslim questioned Mary's virginity and rode ahead.

Ignatius desired to defend Mary's honor by stabbing the Muslim.

He let the mule's choice of roads determine his choice.

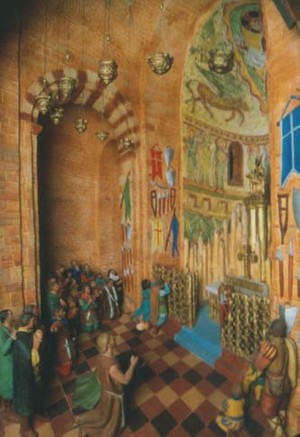

Next, both John W. O'Malley and the Diorama offer the better known story of Ignatius conversion experiences at the Benedictine monastery of Montserrat where he undertook a vigil before the famous Black Madonna statue in the basilica. In spite of the fact that Ignatius legs were not fully recovered from his battle wounds, he determined to extend a traditional chivalrous act toward Mary. Ignatius maintained his vigil of arms, standing for the entire night. He then made the commitment to become a man of peace, laying his sword and dagger down in surrender before the Black Madonna.8

Vigil at Montserrat in 1522 (diorama)

Vigil of Arms standing all night before the altar of Our Lady of Montserrat, The Black Madonna.

Surrendered his sword and dagger for a pilgrim's staff and beggar's clothing.

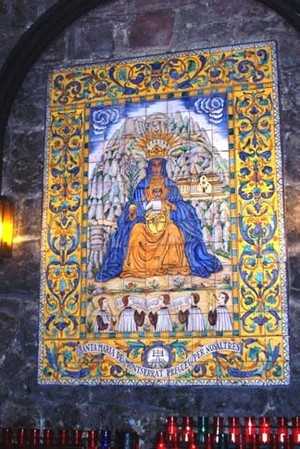

The Black Madonna at Montserrat

Ceramic Tile Artwork at Montserrat of Black Madonna

Continuing on his way to Jerusalem from Montserrat, Ignatius journeyed to Manresa where he wrote the Spiritual Exercises during lengthy meditations in a cave. The Spiritual Exercises became the foundation piece of the Society of Jesus. The cave of Ignatius meditations was enclosed by a marble wall and is now a small chapel replete with a wide variety of grand works of art. Although several pieces of artwork, including the one within the altar of the Manresa cave itself, show Ignatius looking up at Mary while he writes the Spiritual Exercises in the cave, to date we have not found supporting textual documentation of that vision of Mary. Mary is, however, frequently cast as intercessor in the Spiritual Exercises. For instance, The Third Exercise suggests a series of colloquies, with the first to be addressed to Our Lady. The colloquy asks for her to intercede with Jesus Christ.

This is to be made to Our Lady, so that she will obtain for me grace from her Son and Lord for three things, (i) that I may feel an interior knowledge of my sins and an abhorrence for them, (ii) that I may feel a sense of the disorder in my actions, so that abhorring it I may amend my life and put order into it, (iii) I ask for knowledge of the world so that out of abhorrence for it I may put away from myself worldly and aimless things. Then a Hail Mary.9

Similarly, in the Meditation on the Two Standards, Ignatius recommends another colloquy, which also asks for Mary to intercede with Jesus so that the reader may obtain physical and spiritual poverty, receive insults and reproaches, and the capacity to accept these without sin. Mary appears as well in the First Day: First Contemplation on the Incarnation, where Ignatius exhorts his reader to reflect upon Gabriel's appearance to Mary in the annunciation story.11

Influence of Mary on Spiritual Exercises

St. Ignasi de Loiola, Cova de Manresa.

Ignatius writing the Spiritual Exercises in the cave at Manresa with the Manresa bridge and the Montserrat mountains in the background.

Altar Relief in Manresa Cave of Mary's Influence on Ignatius While Writing the Spiritual Exercises

The Loyola Castle Diorama text closes by stressing again the role of Mary in Ignatius' life. Reflecting about what it means to be a Jesuit, the narrative suggests that Jesuits should emulate Ignatius, who prayed to Mary without ceasing to place him at the side of Jesus, her son. Investigating this kind of devotion in the life of Ignatius, we discovered numerous instances of Ignatius entreating Mary to intercede with God or Jesus to enhance his relationship with the deity. Particularly notable in this regard is The Spiritual Diary, in which Ignatius asks Mary to intercede on his behalf with God. Throughout The Spiritual Diary Ignatius perceives Mary as very receptive to him. In his meditations, he sees her as highly willing and ready to intercede with God.12 So central is Mary in this role of intercessor in the Diary that Ignatius recalls his meditation during the Mass of Our Lady in the Temple, saying, I could not but feel or see her, as though she were part or rather portal of that great grace that I could feel in my spirit.13 In some of Ignatius letters, his devotion to Mary is evident, as he indicates his intention to pray to the Mother on behalf of the addressee.14 On a number of occasions in the Autobiography, Ignatius speaks of Marian visions or of further devotion to and communication with the Madonna. In the Epilogue to the Autobiography, Gonçalves da Câmara relates how Ignatius envisioned Mary or received confirmation from her throughout the forty days during which he meditated upon the Constitutions.15 The pilgrimage, the readings that had been suggested as background for the pilgrimage, and especially the Diorama at Loyola Castle opened up to us an important aspect of Ignatius spiritual life.16 Mary continued to be a very influential figure throughout Ignatius spiritual journey. Our discoveries about this influence along with the diverse representations of Mary that we encountered fueled an interest not just in Mary, but in the role of women in general in the life of Ignatius and the early Jesuits. During the pilgrimage, we heard stories about Ignatius and women from tour guides and other pilgrims. From the confluence of all this, we began to focus on some areas of special interest to us beyond Ignatius? devotion to Mary including the secret ordination of one woman, Princess Juana of Austria, into the Society of Jesus very early in its history.17 In addition, we discovered information about an early Jesuit affiliated order composed of a handful of women who were engaged in the ministries to prostitutes under Ignatius himself. Unfortunately, as a result of some difficulties within these interactions with women who wanted to join the Jesuits, Ignatius approached the Pope who granted them a decree in 1547 freeing the Jesuits from the spiritual direction of women which has lasted almost 500 years.18 Ignatius devotion to Mary and her extraordinary influence upon his life were unknown to us prior to the pilgrimage trip, either as Jesuit university faculty or as Protestant feminist scholars. To Dr. Melcher, as a biblical scholar, this was a source of great consolation, to use Ignatian terminology. To Dr. Heydt, as a clinician and social worker, the consistently empowering portrayals of Mary were of greater interest. As two feminist professors teaching within a Jesuit institution for nearly ten years at the time, we pondered how it is that this aspect of Ignatius spiritual development seems to have received much less attention than many other elements, such as his relationships with other early Jesuits. Uncovering the secret agency of Mary as a hidden catalyst in the formation of the Society of Jesus through her influence on Ignatius was an exciting as well as puzzling discovery. While it was personally gratifying to make the discoveries recounted here, as professors we believe that the implications of these discoveries for Ignatian education serve as an example of how uncovering lesser known herstory through the experiential learning of a pilgrimage sparked new insights into both history and herstory. As feminists and educators have discovered through the decades, experiential learning can be a crucial means for instilling a more holistic education in which the learner gains understanding in both cognitive and affective ways. Although the focus here is on the diverse, complex images of Mary in Spain and Rome and especially on the influence of Mary in the devotional life of St. Ignatius of Loyola, the fuller version of our paper explicates other important details of the influence of women in general on the early Jesuits. The impact of this on us is developing in unexpected ways that contribute to new understandings about how Jesuits and feminists can embark together on means for the Society of Jesus, for Jesuit education, as well as for education in general, to proceed towards greater inclusion of women at every level, including in relating its history. Both our reflections and research emphasize the need for greater recognition of the historical role of women in the development of the Society of Jesus.

Through the pilgrimage, the early stories about women and the Society of Jesus offered historical lessons that can aid in seeking greater solidarity among the Society, Jesuit institutions, and the many women like us who contribute to the Jesuit mission on a daily basis. We provide this reflection to stress the value of incorporating such experiential learning in the future in Jesuit institutional contexts, especially towards the end of making these contexts more inclusive. After nearly 500 years of silence, the ground breaking nature of Decree 14: Jesuits and the Situation of Women in the Church and Civil Society must be emphasized. Emanating from the 34th General Congregation of the Society of Jesus in 1995, this amazing call for solidarity with women officially recognizes Jesuit complicity with the church and society in gender discrimination against women. Our research indicates, however, that when individual Jesuits take that brave step to truly align with women in solidarity, trouble tends to brew for them and women themselves or the history of their roles again are omitted. In conclusion, we suggest that substantial and consistent support must come from Jesuit leaders and educational institutions to amplify the importance of the role of Mary within its historical documents and to further explore how the Society can obtain greater solidarity with women, in keeping with the stated intent of Decree 14.

Ignatius Cradling Mary

(Loyola Castle)

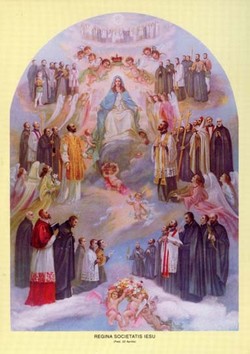

We leave you with two final images from our pilgrimage. Within the Loyola family castle was found one of the most powerful Ignatius-Mary images of all: a life-sized statue of Ignatius cradling a doll-sized full-bodied statue of Mary attired in flowing blue and white, as seen on the left. Below is a postcard replication of a painting within the Gesù in Rome portraying one of the most powerful images of Mary along with several of the early Jesuits. The title of the painting, Regina Societas Gesu translates as the Queen of the Society of Jesus. A translation of the verse on the other side of the postcard follows. Through the pilgrimage to Spain and Rome, experientially engaging with such diverse but lesser known representations of Mary as agent and uncovering her role as a hidden catalyst to Ignatius spiritual journey urged us to further research the role of herstory in Jesuit history. As well, the pilgrimage was spiritually empowering to us as women, as feminists, and as professors in a Jesuit institution of higher education. In addition to encouraging engagement in similar avenues of experiential learning, these reflections are shared in the hopes of stirring others to make similar discoveries, to dust off Decree 14, and to continue taking brave steps toward the kind of solidarity envisioned therein.

"Regina Societas Gesu" Postcard: statement on the back (translation)

"O God, that you have given us as our Mother and Queen the Virgin Mary, from whom Christ your child was born, through her intercession give us glory promised to your children in the kingdom of heaven."

- 1 Louis A. Bonacci, S.J., The Marian Presence in the Life and Works of Saint Ignatius Loyola: From Private Revelation to Spiritual Exercises The Cloth of Loyola's Allegiance. Doctoral Thesis in Sacred Theology. International Marian Research Institute, University of Dayton, 2002, 16-17.

- 2 James W. Reites,Ignatius and Ministry with Women,The Way, Supplement 74 (Summer 1992): 7-19(7).

- 3 This painting's influence on Ignatius is reflected in Hugo Rahner, S. J., Saint Ignatius of Loyola: Letters to Women (Freiburg: Herder, 1959), 116.

- 4 Joseph A. Munitiz and Philip Endean, Saint Ignatius of Loyola: Personal Writings (London: Penguin,1996), 16.

- 5 Ibid., 18.

- 6 William J. Young, S. J., translator, Letters of St. Ignatius of Loyola (Chicago: Loyola University Press, 1959), 349-50.

- 7 Munitiz and Endean, Personal Writings, 19.

- 8 Ibid., 20. See also John W. O?Malley, The First Jesuits (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1993),24-25.

- 9 Ibid., 297-98.

- 10 Ibid., 311-12.

- 11 Ibid., 305-06.

- 12 Ibid., 74, 77, 78, 81, etc.

- 13 Ibid., 78.

- 14 For example, see Young, Letters, 11.

- 15 Munitiz and Endean, Personal Writings, 64.

- 16 Two standard texts had been suggested to all on the pilgrimage: John W. O'Malley's The First Jesuits (1993) as well as Saint Ignatius of Loyola, Personal Writings: Reminiscences, Spiritual Diary, Select Letters including the text of the Spiritual Exercises, translated by Joseph A. Munitiz and Philip Endean (1996).

- 17 For more information about this ordination and the circumstances surrounding it, see Fr. John Padberg, S.J., Secret, Perilous Project, Company Magazine 171 (1999) and Joan Roccasalvo, C.S.J., Ignatian Women Past and Future,Review for Religious 62 (2003): 38-62.

- 18 Rahner, Letters to Women, 290.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Bonacci, Louis A., S.J.,The Marian Presence in the Life and Works of Saint Ignatius Loyola:

From Private Revelation to Spiritual Exercises The Cloth of Loyola's Allegiance. Doctoral Thesis in Sacred Theology. International Marian Research Institute, University of Dayton, 2002.

Decree 14 http://www.sjweb.info/documents/sjs/docs/Dr%2014_ENG.pdf

Diorama text, French version, Loyola Family Castle, Loyola, Spain. (English translation by Sarah Melcher, October, 2006). Further source explanation follows in the opening words of the text which is written in the second person.

In this exposition, you are able to contemplate the most significant events from the life of Iñigo Lopez de Loyola who would subsequently become Saint Ignatius of Loyola. The sculptor George Serraz is the composer of these 25 episodes which constitute the Diorama.

Munitiz, Joseph A. and Endean, Philip. Saint Ignatius of Loyola: Personal Writings. London: Penguin, 1996.

O'Malley, John W. The First Jesuits. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1993.

Padberg, John, S.J. Secret, Perilous Project, Company Magazine 17 (1999).

Rahner, Hugo, S. J. Saint Ignatius of Loyola: Letters to Women. Freiburg: Herder, 1959.

Reites, James W. Ignatius and Ministry with Women, The Way, Supplement 74 (Summer 1992): 7-19.

Roccasalvo, Joan, C.S.J. Ignatian Women Past and Future, Review for Religious 62

(2003): 38-62.

Young, William J., S. J., translator. Letters of St. Ignatius of Loyola. Chicago: Loyola University Press.